'Problems happen': Bankruptcy emerges as a viable option for U.S. student loan borrowers

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Student loan forgiveness and bankruptcy are both ideas — and ways — that offer a second chance at what education was originally meant to offer: the American Dream.

If companies declare bankruptcy and bounce back, why can’t people do the same?

“I always wanted to be an attorney when it was time for me to go to undergrad… it was sort of just automatic that I would take out student loan money in order to be able to pay the tuition,” Natalie Jean-Baptiste, an attorney who also specializes in student loans and bankruptcy cases, told Yahoo Finance. “And I didn't really give it much thought it was just what you did.”

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

Jean-Baptiste planned to become an entertainment lawyer: “I got this fire in me, like I’m going to work with rock stars,” she added.

But life doesn’t always proceed as planned, and she was soon paying about $900 a month for her student loans.

She eventually filed for bankruptcy, had her student debt discharged. Through the process, she realized that aside from forgiveness, bankruptcy — even though it was a hard route to take — was a viable option for people. And then she started helping others.

Forgiveness versus bankruptcy

Bankruptcy offers an alternative to the forgiveness plans promised by Congress.

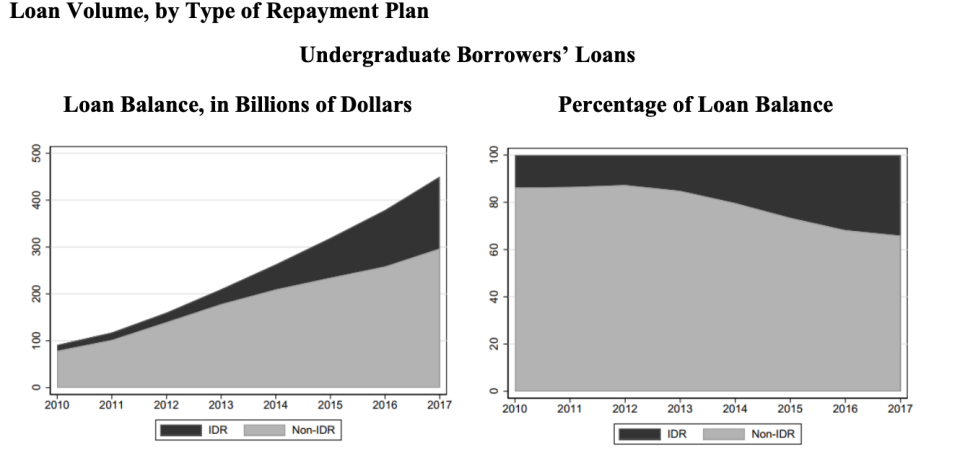

A recent CBO report noted the complexity of such programs: “On the one hand, such plans typically require smaller payments and often allow for loan forgiveness at some point. Those factors would lead to fewer dollars collected. On the other hand, borrowers who make smaller payments accrue more unpaid interest, and the maturity of their loans increases. ... The net effect of those offsetting factors depends on how borrowers’ post-graduation earnings relate to the size of their loans.”

Bankruptcy, on the other hand, was a little more straightforward (in theory — there are many conditions to meet for one to file for bankruptcy and have their loans discharged successfully).

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

“The legal system, for all of its flaws, is a fundamentally fair system,” Austin Smith, a student debt lawyer with Smith Law Group, told Yahoo Finance. “There are problems, but I think that if there's a systemic problem such that is affecting a large number of people, and it is just patently inequitable on its face, there probably is a legal solution to that.”

Smith added that in cases of extreme hardship, bankruptcy “has been part of our legal system for centuries. It's a necessary sort of safety valve and a correction on a financial system that does a lot of good and a lot of ways and has produced a lot of wealth.”

Jean-Baptiste posited that student loan debt can cause extreme hardship, which U.S. courts have begun to acknowledge.

“These people have been struggling under student loan debt for decades, literally,” she said. “And some of them have paid thousands and thousands of dollars on their student loans, but still haven't made much progress — and they're not deadbeats.”

Because “problems happen,” Smith stressed. Life happens. “And when those problems happen, there has to be some kind of escape valve. That's what bankruptcy is supposed to be.”

— Alex Sugg contributed to this story

Transcript

Jim Lehrer (00:00):

Good evening. I'm Jim Lehrer in Washington. Robin is on vacation. One of the ideas to come out of the Great Society from out of the '60s was the notion that everybody who wants a college education should be able to get one somehow, somewhere. Well, that idea has been taking its lumps lately. Escalating tuition costs and skyrocketing operating expenses, along with shrinking endowment funds, bankrupt public treasuries, and increasing complaints about the quality of higher education today.

And now, there's another problem. The federally guaranteed student loan program set up in 1965 to help youngsters go to college, who could otherwise not afford it, has run into some serious snags. An increasing number of students, who have used the program, are not paying back their loans, and the federal government has been left holding the bag.

Aarthi Swaminathan (00:50):

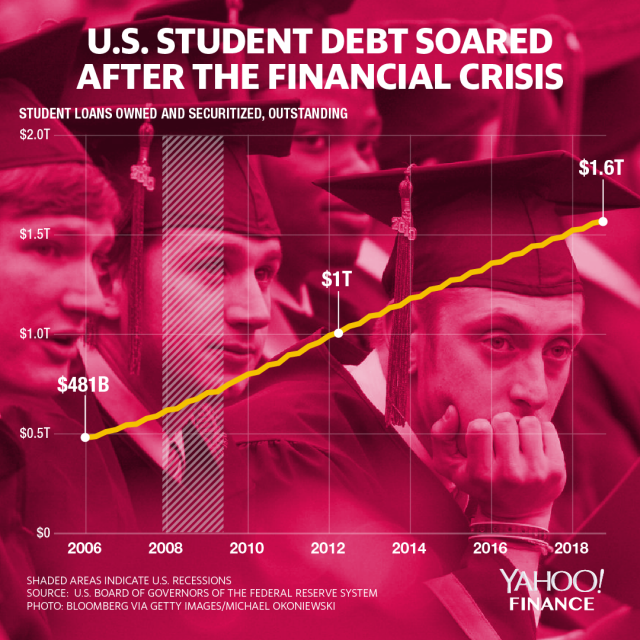

Are you feeling a sense of déjà vu? Because I am. That was from the Robert McNeil Report from 1976. In the previous episode, we looked at how the idea of fairness and the goal of reaching the American dream resulted in the pursuit of higher education. But along the way, that pursuit hit some major potholes as student loan balances became bigger and bigger, and the entire system was just getting unbelievably complicated. In this episode, we find out just how maddening that entire system can get.

My name is Aarthi Swaminathan and this is Illegal Tender season five. Meet Kelly FinLaw. Kelly's an art teacher in New York City. She's been teaching in Washington Heights since January 27, 2007.

Kelly Finlaw (01:44):

College was my only option after high school. My mom made that very clear. She didn't go to college and she always wished that she had. So when we were younger, for my sister and I, she had two rules. "You're going to college and you're going to go live on your own before you get married." So, college was the only option. There was no other way out.

But she also had no money to help us, so student loans were only way. When I was applying for colleges, I went where my sister went. I just followed her there. Every semester I paid for my own college with student loans. I didn't have even one dime that was given to me to pay for college. It was all through student loans. I did get scholarships for my GPA, but not enough to... I mean, clearly not enough to have put me through.

Once I got to college, just thinking about what I wanted to do with my life, it was abundantly clear to me that my art teacher made such an impact on my life. I felt so faith, and more able to be myself in that classroom and just think about how did I want to spend my time and my days on this planet. It made a lot of sense to me to be able to give that to someone else, so I went into art education. It was a five year program, graduated in five years.

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

Aarthi Swaminathan (03:09):

But a few months after Kelly graduated in 2006 with $80,000 in student loan debt, some major moves were going on in D.C. Congress had just passed something called the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program. The pitch was quite simple. You work 10 years as a teacher, as a nurse, a firefighter, you work in public service for the people and we'll help you out with your student loans. You just have to make 120 monthly payments, and then we, the government, will forgive everything else in exchange for your public service.

Kelly Finlaw (03:43):

That program wasn't in existence until the fall of that year. When we came back to school and then it became this is a thing if you're still in. One of my best friends was not going to be teaching. She did not want to and she knew like, "This isn't going to affect me at all." But I knew I wanted to and I was like, "Cool, I'm going to keep doing this thing that I love and in 10 years I will be debt free." I just kept going with what I was doing and believing.

I remember when 2015-16, it was really close. I could see the finish line. I remember thinking, "This huge chunk of my payment is going to disappear." I was so excited. I filled out my paperwork, sent everything in. I remember getting a letter back in the mail, and being so excited to open up that letter, and see, "The rest of your loans have been forgiven. Congratulations."

Aarthi Swaminathan (04:45):

Kelly made 120 payments. She made it slowly, she made it steadily, but she finished it. Kelly was finally going to be debt free, or so she thought.

Kelly Finlaw (04:57):

But it just said, "One of your loans didn't qualify under the program, so you're not approved." I was in my living room and my roommate was there. He's not just a roommate. He's like my little brother. I was so mad, and I was just... He could tell something was wrong and he was like, "I'm really sorry," because I was so mad.

Aarthi Swaminathan (05:26):

A borrower generally takes out not just one, but a bunch of student loans of varying quantities when they go to college. But to qualify for loan forgiveness under that plan that Congress had created and that Kelly had applied for, all of those student loans had to be Direct Loans, which were a special type of student loans that was only owed to the federal government and not to a private lender or to a college.

One of Kelly's loans was not going to qualify. Kelly had to reconsolidate and the clock was reset, another 120 more monthly payments to go. Kelly, along with the 99% of those who had first applied for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, was denied that relief. That promise that Congress had made was broken.

Think about this for a second. Is it fair to offer someone a chance at a debt free life and then take it away from them because they either didn't fill out the paperwork right or they didn't get on the payment plan that was the right one 10 years ago?

But okay, now let's forget everything I just told you about loan [inaudible 00:06:39]. What if I told you that you don't have to make 120 payments and there was another way to get all your student debt erased? I think you've heard of it. It's something called bankruptcy. You file for Chapter Seven bankruptcy. You go through hell and back with the paperwork, and the entire process, and you emerge completely debt free. Is that fair?

Both the idea of student loan forgiveness and bankruptcy raise questions of fairness because they offer a second chance at what education was originally meant to offer, the American dream. If companies can declare bankruptcy and bounce back, why can't people do the same thing? Natalie Jean-Baptiste is a lawyer in New York. She also specializes in student loan bankruptcy. Natalie actually had her own student loans erased or discharged, as the legal term goes, through bankruptcy.

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

Natalie Jean-Baptiste (07:34):

I always wanted to be an attorney. When it was time for me to go to undergrad, I just... My parents didn't have the money to pay for it, but it was just automatic that I would take out student loan money in order to be able to pay the tuition. I didn't really give it much thought. It was just what you did. And so when I graduated law school, I had, I want to say about $170,000 of student loan debt combined between my four years of undergrad and my three years of law school.

Then at that point, I pursued my dream of being an entertainment attorney, and I did that for several years. I got this fire in me like, "I'm going to work with rock stars. I'm going to work in the music industry." That was my dream, and it just didn't work out for me. Financially, it just wasn't making sense. I was trying to pay my dues and climb up the ranks, and become this hot shot entertainment attorney. It didn't work out quite that way.

While I was fulfilled in the fact that I was working for some of the biggest record companies in the world, I still was struggling to pay my dues, and in the sense of making the money that I needed in order to be able to put a meaningful dent in my student loans. I was making substantial payments for a number of years between my private and my federal loans. A combination of about $900 a month, which is what some people pay for a mortgage in parts of the country.

After many years of struggling, almost a decade, it was nine years after I graduated law school, I filed bankruptcy, initially not even expecting to get rid of the student loans. But then I learned about the undue hardship rule and said, "Wow, this is something that I should pursue." I naively endeavored to get rid of student loans when bankruptcy experts were telling me, "Oh no, it's impossible. You can't get rid of student loans. You have to be on your deathbed to get rid of student loans," which is such a myth.

So anyway, after my success in my own case, I decided, "This is what I want to do, and I really want to help other people with this burden and then be a relief, provide them with the relief they need."

Aarthi Swaminathan (10:20):

Natalie isn't the only one. Natalie's had several clients, who she has represented and had their loans discharged in bankruptcy in part or in full over the past few years. It wasn't easy. Lawmakers have made sure of that with various laws that they have created over the years. But it could be done. A big shiny red reset button was available.

Remember Austin Smith from the previous episode? He also specializes in student loan bankruptcy issues. Here's how he explains it.

Austin Smith (10:53):

I think that the legal system, for all of its flaws, is a fundamentally fair system. I mean, there are problems. But I think that if there's a systemic problem, such that it is affecting a large number of people and it is just patently inequitable on its face, there probably is a legal solution to that.

When people have said, I hear over, and over, and over again that, "I called every bankruptcy lawyer in my town. They all said there was nothing they could do for me." I think that is just a depressing way to think about life. I think that there is a way to fix that. There's always going to be some kind of way. It may not be easy, but we can find it.

Very often, their payments are $2,000 or $3,000 a month, and the most they can pay is 200 or 300 or 500 sometimes. At that point, your debt is in what's called negative amortization, so it's just growing, and growing, and growing, and growing every month. And you'll never be able to dig out of that.

That's fundamentally what bankruptcy is for, and has been part of our legal system for centuries because of that. That we understand that it's a necessary sort of safety valve and a correction on a financial system that does a lot of good in a lot of ways, and has produced a lot of wealth, but problems happen. When those problems happen, there has to be some kind of escape valve and that's what bankruptcy is supposed to be.

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

Aarthi Swaminathan (12:18):

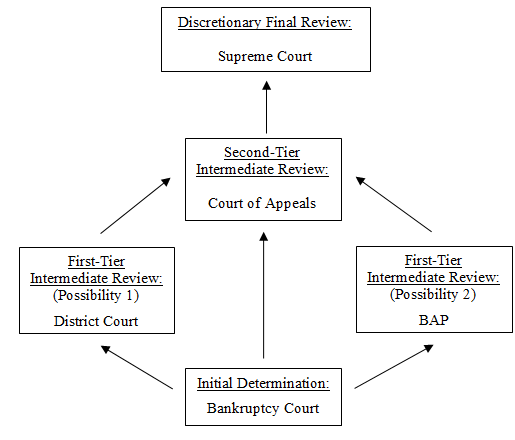

But of course there's a catch. According to Jason Iuliano, an assistant professor of law at Villanova University, each year about 250,000 student loan debtors file for bankruptcy. But most of these people miss a crucial step. They don't file something called an adversary proceeding, which is where they ask the judge to look at their case and make a determination about whether their debt should be discharged. Out of the 250,000 people who file for bankruptcy for student loans, only 400 or 500 people do so every year.

Remember Heather Shade from the previous episode? Heather filed that adversary proceeding. And Heather went through the various conditions that the legal system requires, which is essentially some sort of a test called the Brunner test to show the judge exactly how hard her life has been because of the student loans. Eventually, Heather saw $242,000 in student loans disappear.

But forget about that undue hardship test to demonstrate how student loans are impacting your life. By itself, it's a difficult standard to meet. But to actually get to the adversary proceeding, you have to pay an attorney 1,000s of dollars in fees upfront, and that is if the attorney even takes up your case. But at least there was a way out.

Austin Smith (13:43):

Student loans are in this sort of bizarre category. They began as a government debt, and so they fit within taxes. This is why you can't discharge them because you have to pay back the government. It was only really later that I think they moved into this moral category where people said, "These kids are trying to cheat the system." In some ways, you can characterize everyone in bankruptcy is trying to cheat the system. They did sign a contract to repay a debt and now they are not able to do it. That's not cheating the system. That's life happens and sometimes you can't always honor all of your commitments and that's okay. And there's a place to go to do that and it's called Bankruptcy Court.

Natalie Jean-Baptiste (14:27):

These people have been struggling under student loan debt for decades literally. Some of them have paid 1,000s and 1,000s of dollars on their student loans, but still haven't made much progress. They're not deadbeats. They're people who've tried their best, and they've come to a point where they feel like they don't have another option, like this is their only solution.

Aarthi Swaminathan (14:59):

We've come a long way since 1965 and the Higher Education Act. Are we still talking about education? There are so many problems that have manifested itself over the years in the student loan system that has complicated the idea of higher education, and leading to the quote unquote crisis that we see today.

From the massive rise in college costs, to the increase in student loan balances, and the financialization of these loans, eventually now in the way that the federal government handles that student loan debt, we've heard about some sticky situations. From the outset, it seems like the legal system at least is responding to these student loan borrowers and their hardship and offering them a second chance. Because Kelly Finlaw, remember her, with her student loans, she also ended up in court. Not bankruptcy, but the anger, frustration, and the confusion over her rejected forgiveness application led her to become one of the plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against the Department of Education. She was supported by her union, the American Federation of Teachers. Kelly even appeared on the Hill testifying to lawmakers about her experience.

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about how student loans have wreaked havoc across American finances for decades. Listen to the series here.

Kelly Finlaw (16:17):

After 10 years of making student loan payments, October 2017 was my month, my light at the end of the tunnel. I received a letter from [inaudible 00:16:25] a few weeks later, a letter I had dreamed of for 10 years. I remember standing in my living room when the light at the end of the tunnel went dark. The Department of Education denied my application for Public Service Loan Forgiveness. The reason, which no other loan servicer had ever raised, was that one of the loans was not a Direct Loan.

Aarthi Swaminathan (16:42):

Kelly's case is still ongoing. When we first started working on this season of Illegal Tender, we were corona free. The global pandemic was just developing and we were hearing about cases in Wuhan, in Japan, and very early signs of coronavirus cases in Washington, the state that is. Very quickly the virus spread, and the United States and the rest of the world went through the worst disease outbreak possible in the last 100 years, and we're still going through it.

But when it came down to student loans, the Trump administration and Education Department very quickly took steps to help the majority of the 44 million people who have student loans. To date, they have initiated a 90 day pause on all federal student loan repayments from March 13th, which is when the national emergency was declared, they halted debt collections on all defaulted student loans. They initiated a 90 day pause on all federal student loan repayments starting from March 13th, which is when the national emergency was declared. They halted debt collections on defaulted federal student loans, and they enacted a sweeping 0% interest rate, so that borrowers won't see their loans ballooned during this period.

People consider this move major because pretty soon the unemployment rate picked up higher and higher, and people started seeing their income streams diminish. At least there was one debt less to worry about.

And what does the world look like post COVID-19? That's the next piece of the puzzle we need to figure out. Will people be able to come back online and resume paying down their student loans seamlessly come September 30th? Or will prospective students start to reconsider taking on any student loans or question the idea of higher education as a necessary credential to obtain? We'll just have to wait and see.

Illegal Tender is made by Yahoo Finance at our studios and homes in New York City. This episode was written and hosted by me, Aarthi Swaminathan. Illegal Tender was created, edited, and produced by Alex Sugg. Thank you to Heather Shade, Betsy [Mayotte 00:19:20] Austin Smith, Natalie Jean-Baptiste, Seth [Rothman 00:00:19:24], Kelly Finlaw, Wayne Johnson, and everyone else who I haven't mentioned for sharing your knowledge. If you enjoyed this podcast, head over to Apple Podcasts and leave us a five star rating and review it for the show. Until next time, thank you for listening to Illegal Tender.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.