The coronavirus just doubled the risk of mass bankruptcies

The risk of mass bankruptcies across the U.S. continues to rise as more companies grapple with the fallout stemming from efforts to battle the spread of coronavirus cases, according to one leading bankruptcy professor.

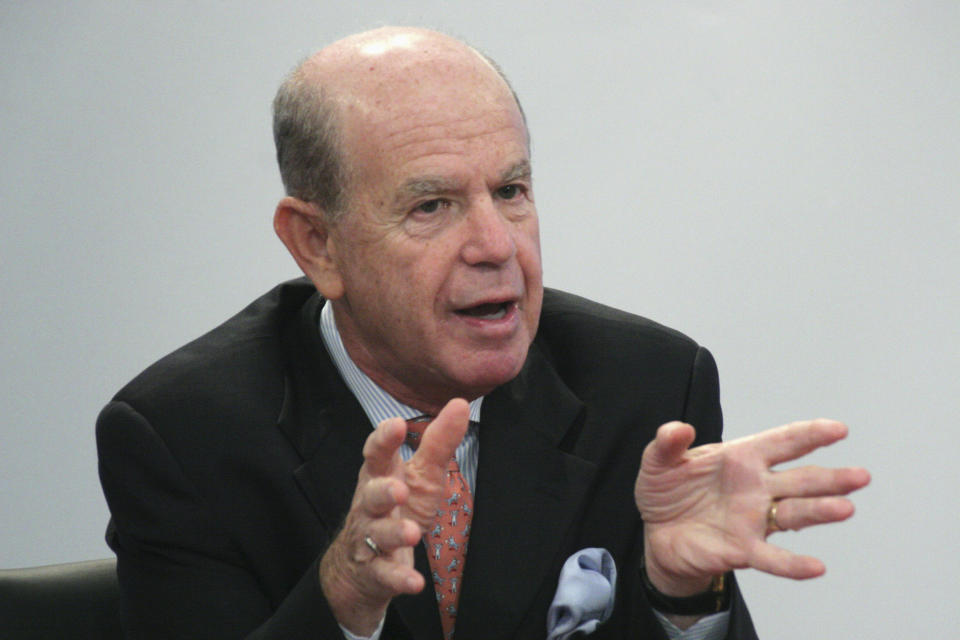

According to data watched by NYU Stern School of Business professor emeritus Ed Altman, bankruptcy and default potential for high-yield companies doubled from 5% to 10% in just a few weeks.

“Today, our numbers are showing a likely default [rate] over the next 12 months of just under 10% that is a huge, unprecedented increase in such a short period of time,” he told Yahoo Finance. “It does signal a crisis in the credit market whenever you get to that 10% level.”

Altman, who pioneered his eponymous “Altman Z-score” as a standardized way of measuring any company bankruptcy’s risk nearly 50 years ago, says distress in the corporate debt market has now reached levels that haven’t been seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

“The distress ratio, which is the percentage of companies whose bonds are selling above 10% more than [comparable] Treasuries, has spiked to around 30%,” he said. “That’s incredible. The only time it has ever been higher was in 2008 [in] December when it was around 80%.”

But perhaps even more alarming than a distress ratio sitting at highs not seen since the Great Recession, is the speed at which things in the high-yield bond market are unraveling. Altman says it took three months for spreads between high-yield bonds and comparable Treasuries to peak, whereas the same thing has happened now in a mere matter of weeks.

“In all my years, I’ve never seen a spread or distress ratio change so quickly by so much,” he said.

To its credit, the Federal Reserve has moved quickly to address stresses already stemming from mounting levels of corporate debt, enacting a new facility to directly purchase eligible corporate bonds from investment grade issuers.

But as things get worse, Altman points out there is another danger looming in the form of inevitable credit rating downgrades, which could force some investors to shed their holdings if they aren’t allowed to invest in non-investment grade rated debt. Casino operator Las Vegas Sands, for example, is teetering on a BBB- rating from S&P Global Ratings, which means a downgrade would thrust its debt into junk status. Altman says credit agencies are wrong to estimate that only 10% of those companies on the brink will eventually dip into junk status.

“My analysis showed using the Z-score method that more than 30% of the BBB’s already look like non-investment grade companies and that the impact would be much greater than this 10%,” he said. “If it was followed by a recession, there’s no question in my mind this would be the worst period for corporate default amounts that we’ve ever seen.”

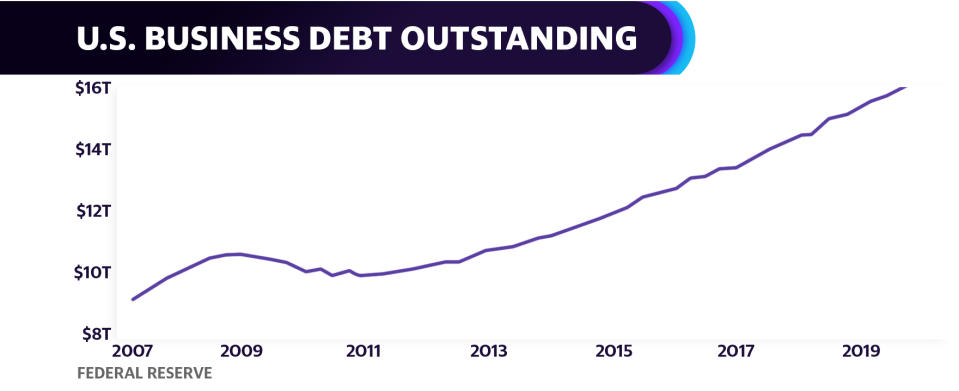

To be sure, Altman posited that default rates wouldn’t likely hit record levels, but total default amounts would due to high outstanding corporate debt before the coronavirus crisis began. A low interest rate environment had long fueled corporate borrowing. Since the financial crisis, corporations have issued about $1.8 trillion in new bonds globally each year, a rate that was about double issuances over the prior seven years.

“In other words, there was great big debt balloon that peaked right at the beginning of this year — at probably more than 48% to 49% of GDP for non-financial corporate debt,” Altman said. “We estimate today probably in the high-yield bond market something like $150 billion in corporate defaults, and that’s not even counting the loan market which has also grown dramatically.”

High-risk companies

Some of the measures taken by the Fed and potential relief in the form of corporate bailouts on the fiscal side could help prevent a wave of bankruptcies, but some companies will need more help than others. To use Altman’s own scores of financial stress as a proxy, companies with a rating below 1.1 fall in the so-called bankruptcy risk zone, while companies above 2.6 are not at risk.

Restaurants, which have been hit hard due to stay at home orders, range from Outback Steakhouse owner Bloomin Brands (BLMN) at a 1.38 rating to Olive Garden owner Darden Restaurants (DRI) at 2.59. On a sector basis, Altman also singled out energy as a high-risk for experiencing a high volume of bankruptcies in the short term.

“We’ve seen a very large percentage of these oil and gas companies that were already in these zones even before the drop of oil prices to very low level prices of $22 to $23 a barrel,” he said. “They will be gone very quickly into bankruptcy.”

Zack Guzman is the host of YFi PM as well as a senior writer and on-air reporter covering entrepreneurship, cannabis, startups, and breaking news at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @zGuz.

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Read more:

Why the US shouldn’t cheer the crash in oil prices like Trump just did

Coronavirus causes Sir Richard Branson to postpone the launch of his new Virgin Voyages cruise line

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.