Exclusive: Facebook ex-security chief: How ‘hypertargeting’ threatens democracy

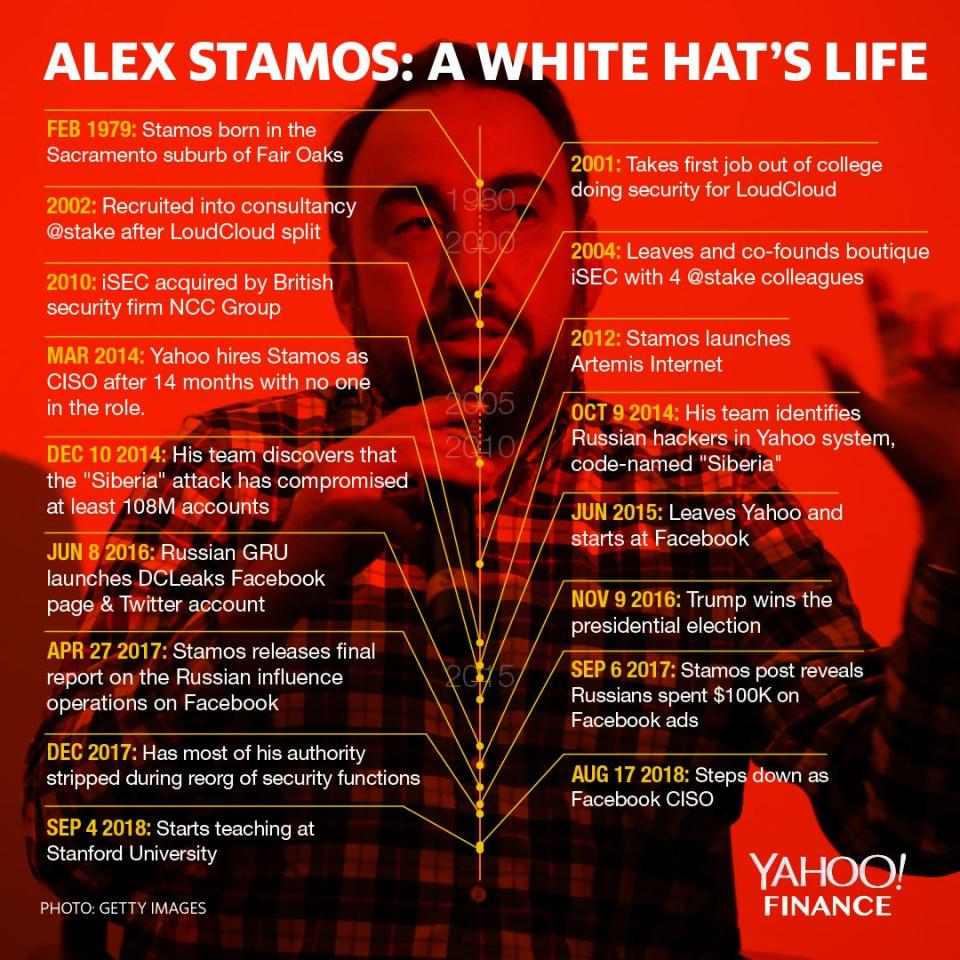

In October 2018, Alex Stamos, whose highest degree is a BS in computer science and electrical engineering, delivered his first academic lecture.

It was the Sidney Drell Lecture at Stanford University, named for an august physicist and arms control expert. It’s the event of the year at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. Stamos’s four immediate predecessors at that podium were a former director of the National Security Agency, two U.S. Secretaries of Defense—one former, one sitting—and Vint Cerf, the co-inventor of the fundamental architecture of the internet.

Then 39, Stamos had just stepped down as Facebook’s chief security officer in August—after having been stripped of most of his authority nine months before that. Though Stamos generally favors jeans, flannel shirts, and Ecco loafers, he looked resplendent that night in a well-tailored, corporate suit, a uniform he’s learned to wear credibly at board committee meetings and Congressional hearings.

“Looking around the room,” he said nervously as he began, “it’s pretty clear that there are some differences between this audience and the hacker conferences I feel more comfortable speaking at. Not just in academic credentials, but most obviously in the amount of body piercings.”

Despite the incongruities, Stamos was the obvious choice for the speech, says Amy Zegart, a senior fellow at both CISAC and the Hoover Institution. While Drell had devoted himself to averting the national security challenge of his era—nuclear war—Stamos has battled with one of the paramount security threats of ours: cyberwarfare. For that reason, she’d wanted to lure Stamos to the university for almost three years, she says. When he became available, Stanford cobbled together an interdisciplinary, policy-cum-research-cum-teaching post just for him, notwithstanding his lack of any advanced-degree parchment to adorn his office wall. (He hangs his five patents there, instead.)

“Alex is a unique person in all respects,” says Nate Persily, a Stanford law professor who also heads the university’s Project on Democracy and the Internet. “There are very few people like him in their deep knowledge of the multiple challenges that technology is posing for society. He gave this incredible talk to my class mapping the information warfare environment. He’d say, this is what this country does. This is what that country does. The entire talk was brand new to me. You realize he is just this repository of information very few people have.”

‘Rough around the edges’

This is a profile of Stamos—a complex man we will be hearing about, and from, for years to come. Over the past three months, Yahoo Finance has spoken with 19 people who have known him professionally over the course of his career—at Facebook; during his stormy tenure before that as Yahoo’s chief information security officer; and, still earlier, as an outside consultant for the likes of Microsoft, Google, and Tesla. (Some requested anonymity, either because of employer policies, non-disclosure agreements, protective orders, or other considerations.) Over that same period Stamos also sat down for three in-depth interviews—at his cramped Stanford office, at a casual, bus-your-own-plate eatery not too far away, and, lastly, at his airy, colonial-eclectic, $3 million home in the hills of a Silicon Valley community he asked Yahoo Finance not to identify.

Stamos is no shrinking violet. He publishes op-eds; launches contrarian, pugilistic tweets to a following of nearly 48,000; and now has a gig as an NBC analyst. He is best known, though, for his stint at Facebook during what turned out to be a historic moment of cultural epiphany. He was at ground zero just as the free world began asking itself the urgent question Persily posed in a scholarly article: “Can Democracy Survive the Internet?”

But cyberwarfare, fake news, and internet-based propaganda continue to pummel and menace our culture. That means that Stamos, with his unique skill sets, honed during an unduplicatable career path, will remain in the headlines, too. Stamos also reveals here, more candidly than ever, why he left Facebook, the mistakes he made there, which criticisms of Facebook miss the mark, and what he thinks are the true threats to democracy posed by social media. As we’ll see, he takes aim, in particular, at the opaque “hypertargeting” of campaign ads. He’s less concerned about what Cambridge Analytica did in the past than about “the 20 Cambridge Analyticas that still exist,” lawfully buying their data from other sources today.

From his colleagues, a picture emerges of an inspiring, but polarizing figure. There’s a reason Facebook nudged Stamos toward the exit door. Some former colleagues—including many who still revere him—acknowledge that he is “impolitic,” “volatile,” “dogmatic,” “a self-promoter,” “exhausting,” “rough around the edges,” “not the greatest manager,” “short-tempered,” and, above all, “unfiltered.”

In fact, these are strengths, some claim, because they’re what give him the “cojones” to speak truth to power, as one puts it.

But they take their toll.

“In some situations he lacked political skills, so he wasn’t as effective as he wanted to be and needed to be,” says someone who worked with him at Facebook.

“Alex is very smart and passionate,” says a former senior official at Yahoo, previously Yahoo Finance’s parent company. (Verizon Media now owns Yahoo properties, including Yahoo Finance.) “But he can be so passionate—so hyped up, so emotional—that it could be difficult to distinguish threats that were critical from those that were much less so. That was tough, given the importance of his role.”

Roughly speaking, Stamos is more admired in information security circles than in traditional corporate ones. Basically, the security people feel they know what he’s up against, while corporate people, for whom cybersecurity was just one of many competing concerns, think he’s “immature” and “not a team player.”

The fact that he quit Yahoo in a rage, after just 14 months, and that his rocky stay at Facebook ended unhappily, actually redound to his favor among some infosec types. In January 2017, influential tech writer Cory Doctorow called Stamos a “human warrant canary,” because, as Doctorow understood matters, he’d quit Yahoo rather than countenance unethical conduct. (A “warrant canary” is an indirect, wink-wink way that an ISP can signal to users that the FBI has obtained a court-order to surveil their accounts, though the order forbids directly alerting the user.)

Doctorow’s view seemed to be reinforced in November, when The New York Times published a deep-dive investigation of Facebook’s attempts to downplay Russia’s exploitation of its platform for election interference. The lede of the story (“Delay, Deny, and Deflect”) portrays the then-recently-departed Stamos as one of the very few good guys there.

“‘You threw us under the bus,’ [Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg] yelled at Mr. Stamos,” the article recounts, after Stamos had given the company’s audit committee an unexpectedly unvarnished account of the extent of the Russian interference. (Stamos has said that he doesn’t remember those words. A Facebook source says executives were “frustrated Alex had not shared his conclusions with leadership or even his manager or colleagues before going to the board.”)

Some corporate types, on the other hand, reacted differently to the article.

“He’s doing to Sheryl what he did to Marissa,” says one corporate consultant—nearly shouting over the phone in alluding to former Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer. This consultant had advised Yahoo when it was dealing with the fallout from a 2014 state-sponsored intrusion at that company—one of the largest ever. That hack, which occurred during Stamos’s watch but wasn’t disclosed until September 2016, long after he departed, left the company awash in class-action suits and an assortment of probes led by the Securities and Exchange Commission, Department of Justice, and state attorneys general. Former CEO Mayer testified to Congress in November 2017 that she only learned of the key theft of data—estimated to have impacted 500 million user accounts—nearly two years after it occurred.

Nevertheless, in April 2018, an SEC inquiry found that Stamos and his team had, in fact, informed Yahoo’s “senior management and legal teams” of the key theft “within days” of finding out, in December 2014. An independent board inquiry reached murkier conclusions, but even it acknowledged, in March 2017, that Stamos’s group had provided the “legal team … sufficient information to warrant substantial further inquiry in 2014,” though the legal team “did not sufficiently pursue it.”

Though Stamos does see his departure from Yahoo as reflecting matters of principle, he does not see his Facebook exit in the same light. He offers nuanced views about the company’s missteps over the past several years, defending the corporation more than he criticizes it. He also describes his departure from Facebook in wistful terms, admitting having misplayed his cards. Facebook declined to comment for this piece, other than to refer Yahoo Finance to a statement COO Sandberg issued when Stamos’s departure was first announced last April: “Alex has played an important role in how we approach security challenges and helped us build relationships with partners so we can better address the threats we face. We know he will be an enormous asset to the team at Stanford and we look forward to collaborating with him in his new role.”

(Though Stamos’s severance contract contains a non-disparagement clause, Stamos says he has since received written permission from Facebook’s general counsel to speak freely of his time there. A research institute he is now launching at Stanford—focusing on social media and elections—may eventually seek funding from Facebook, he acknowledges, just as it may solicit funds from other companies and nonprofits.)

At Facebook Stamos misplayed the “Game-of-Thrones-y stuff,” he says. It wasn’t so much that he alienated COO Sandberg or CEO Mark Zuckerberg, he says, but that he offended laterally situated people with his lack of guile and tact. Those people, with many more years at the company, had Zuckerberg’s ear and loyalty, he believes—a view shared by another Facebook employee who was there at the time.

Says Stamos: “A legitimate criticism that I’ve heard is, ‘Alex, you can’t just be right.’ … I didn’t come up in the corporate world. My job as a consultant was to be 100 percent perfectly honest. These guys in the corporate world learn about how to effect change passive-aggressively, right? Without being in people’s faces. And I’ve never learned that skill. So I pissed them off.”

The letter from the NSA

Stamos was born in the Sacramento suburb of Fair Oaks in February 1979. He is the son of an orthodontist and a homemaker. His ethnically Greek grandfather, a goatherder’s son, immigrated from eastern Cyprus after World War II with a fifth-grade education, Stamos recounts. He got a job as a lineman with AT&T and, by the 1990s, worked his way up to engineering manager in PacTel’s Sacramento office.

Whether in class or in interviews for this article, Stamos speaks quickly, occasionally slipping into burst-fire mode where words become so compacted as to be unintelligible. He speaks of inmationscurty (information security) or yesP devices (USB devices) or the ausraliansigdirectorate (the Australian Signals Directorate—its NSA, basically). At the same time he is apt to forget that a lay listener can’t instantly process all the acronyms and code names that pepper his narratives: PLA, FSB, SVR, GRU, APT1, ECPA (pronounced Ek-pa), Aurora, Lazarus, and on it goes.

“So I was seven or eight when wegottacomder64,” he narrates—i.e., “when we got a Commodore 64.” He used the family’s dial-up modem to access BBSes (bulletin board services). “I kind of taught myself from these groups what was early hacking. Just taking over forums, breaking into other people’s BBSes and stuff.”

Nothing malicious. “But as a teenager,” he continues, “if you were interested in this kind of stuff, you had no legitimate outlet, right?”

Like most security people of his generation, Stamos is largely self-taught and peer-taught. The security industry is only about 30 years old, with most people dating its origin to the release of the Morris Worm in 1988. When Stamos was growing up, not only did formal courses not exist, but the technology was evolving so fast that books couldn’t possibly keep up.

By his senior year of high school, Stamos’s skills were drawing attention. He received an unsolicited letter from the National Security Agency, he recounts. It was offering him a full college scholarship in exchange for a ROTC-like commitment to work for it afterward.

“Which is really creepy,” he says, “because you have no idea how they found you.” He turned them down and went to the University of California at Berkeley. Though he also got into Stanford, he adds, he chose Cal because they offered him a full scholarship and, also, because of the atmosphere. While Stanford seemed “calm and chill,” the Berkeley campus was “total chaos,” he says. “I’d grown up in a suburb, so this was it.”

In college he finally got some formal computer science training. But peer-training from hacker conferences was crucial. Jeff Moss, a/k/a The Dark Tangent, had launched the first DEF CON conference in 1993, with about 100 people in attendance, Moss estimates. As a gauge of how the community has grown, the most recent one, in 2018, drew 28,000.

In the summer of 1997, just before Stamos started college, his father took him to DEF CON 5—Stamos’s first—in Las Vegas. Stamos wasn’t yet old enough to rent a room.

Already by then, though, it wasn’t just kids with blue hair showing up. Big companies, like Microsoft, and government agencies had started sending employees there. Seeing an opportunity, Moss started a second, more expensive series—called Black Hat Briefings—which catered to these grownups. Stamos would later attend those, too, once he started drawing an income. (Though Moss sold Black Hat in 2005, he still runs DEF CON. He also holds other positions, which hint at how important these conferences turned out to be. Now 44, Moss serves on the Council on Foreign Relations, the Cyber Statecraft Initiative of the Atlantic Council, and the U.S. Homeland Security Advisory Council.)

Hacker “lunch and learns”

Upon graduation in 2001, Stamos got a job doing security at LoudCloud, a pioneering cloud computing company. There Stamos worked with an outside security boutique called @stake, which was one of the two leading such outfits of the era. When LoudCloud split in two in 2002, with Stamos’s half being acquired by Electronic Data Systems, Joel Wallenstrom of @stake recruited Stamos to join.

“To be successful at @stake,” Wallenstrom recalls, “you needed to be a Swiss Army knife across all layers of computing. That’s what made Alex so successful. He has full-stack understanding of what is happening, from building on bare metal to using any sort of cloud service to you name it.” Wallenstrom is now CEO of Wickr, a heavily encrypted messaging app.

At @stake, Stamos continued his education.

“We had ‘lunch and learns,’” recalls Katie Moussouris, who worked there at the same time as Stamos. Some of the best hacking minds in the country would share their knowledge. Moussouris later moved to Microsoft and now leads her own firm, called Luta Security. She has become a nationally recognized authority on bug bounties—programs whereby companies or agencies offer rewards to hackers for responsibly reporting vulnerabilities in their infrastructure. Moussouris has set up such programs for the Department of Defense, including “Hack the Pentagon.”

Stamos’s biggest client at @stake was Microsoft. “It was an amazing experience,” he recalls. “We got to work on XP SP2 and Windows 2003, which were kind of Microsoft’s first stabs at fixing the security problems that had accrued over a decade.”

In 2004 Symantec, which was then embroiled in a legal dispute with Microsoft, acquired @stake. “Microsoft kicked my team off campus that day,” Stamos recalls, because of potential conflicts.

It was a great opportunity. He, Wallenstrom, and three other @stakers split off to found their own boutique, called iSEC, with Microsoft as an anchor client. A second early client was Google, which launched a product it called Gmail that year.

Bliss was it in that dawn to be an infosec geek. Interactive e-commerce, or Web 2.0, was in its infancy. “So a lot of security issues inherent in that model were just being discovered and researched,” says Heather Adkins, who joined Google in 2002 and is now its director of information security and privacy. “Alex and the team he built were at the forefront of identifying and battling that.”

iSEC was a classic startup, composed of 20- and 30-somethings who couldn’t even afford an office. Stamos had gotten married in 2003, and his wife’s clothes closet doubled as the firm’s server closet. He remembers draping a shoe rack over the server to dampen the whirring noise at night. (Today, Stamos and his wife, a teacher, have two boys and a girl, ages 11, 9, and 7.)

Now directly interacting with clients, Stamos had to master the interpersonal challenges of his job. He was constantly a bearer of bad news. Security consultants had to warn clients of major risks they were running unless they invested large sums of money on fixes.

“We’re kind of in the business of telling people that their babies are ugly,” says Wallenstrom. “Alex was pretty good at that.”

It’s fitting, Stamos notes to me in an aside, that had he been born a girl, his mother had planned to name him Cassandra. (In Greek mythology, Cassandra was a seer who issued accurate prophecies of doom that no one listened to.)

Aurora: A Chinese state-sponsored intrusion

Over the years, iSEC picked up more blue-chip clients, including Oracle, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Tesla, and Facebook. Stamos’s assignments expanded beyond the nitty-gritty of malware and penetration testing, and brushed up against bigger public policy issues. In 2010, when Google got in trouble with European privacy authorities for its Street View data collection practices, it hired Stamos to oversee the forensic destruction of the offending files. (“A shredder that can eat a hard drive is a very scary machine,” Stamos observes.)

In 2009 he got his first exposure to state-sponsored intrusions. Google discovered that it had been subjected to a series of attacks—now known as Operation Aurora—by a team of highly persistent Chinese hackers. (A few years later the security firm Mandiant identified them as having come from two units of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.) Google, which publicly revealed the attacks in January 2010, also came to realize that the intruders had infiltrated at least 20 other companies, as well. Google’s Adkins referred many of those companies to Stamos for help, she says.

These assignments eventually took Stamos to the National Counterterrorism Center in Liberty Crossing, Virginia. “We did a briefing for DNI [the office of the Director of National Intelligence] on, basically, this is what we’ve learned about Chinese tactics from what we’ve seen.”

From his discerning perspective, were state-sponsored hackers a marvel to behold? That’s actually a misperception, he responds. They aren’t necessarily “head and shoulders above other adversaries,” he explains. “The big difference is that the attack doesn’t have to be economically viable, or end in monetization. So they can put months and months into breaking into a company with no end in sight.”

In late 2010, iSEC was acquired by the British security firm, NCC Group, but otherwise the group continued operating much as before. Then, in 2012, Stamos launched an ambitious internal startup within NCC called Artemis Internet. He wanted to create a sort of gated community within the internet with heightened security standards. He hoped to win permission to use “.secure” as a domain name and then require that everyone using it meet demanding security standards. The advantage for participants would be that their customers would be assured that their company was what it claimed to be—not a spoof site, for instance—and that it would protect their data as well as possible.

The project fizzled, though. Artemis was outbid for the .secure domain and, worse, there was little commercial enthusiasm for the project.

“People weren’t that interested,” observes Luta Security’s Moussouris, “in paying extra for a domain name registrar who could take them off the internet if they failed a compliance test.”

From Edward Snowden to Aaron Swartz

In June 2013, highly classified information from the National Security Agency, leaked by former government contractor Edward Snowden, began to appear in articles in The Guardian, The Washington Post, Der Spiegel, and The New York Times.

The revelations roiled the tech world and opened a rift of distrust between Silicon Valley and the U.S. intelligence community. Beyond the civil liberties issues raised by surveillance of U.S. citizens, tech companies were shocked that the NSA had been exploiting vulnerabilities in their infrastructure for years, rather than reporting them promptly, so the companies could fix them.

Stamos was among the outraged. “The Snowden documents demonstrated that all they cared about was gathering information from America’s enemies. None of their interest was in actually making American technology or companies safer.”

To be sure, his reactions were nuanced. “It’s not like I was just anti-cop,” he says. As a consultant, he had helped gather evidence that was used to prosecute bad actors.

On the other hand, he had also been retained as a defense expert in a couple cause celebres in the hacking world, including the hugely controversial federal criminal prosecution of Aaron Swartz, who helped create Reddit. In January 2013, Swartz, who was facing felony charges for having broken into MIT’s servers in an attempt to create a free internet archive of scientific journals, had hanged himself. He was 26.

Stamos went to Swartz’s funeral in Chicago. “That was radicalizing,” he recounts.

In December 2013, wrestling with these emotions and conflicting impulses, he delivered a talk at DEF CON 21, entitled “The White Hat’s Dilemma.” In it he talked about the Hippocratic Oath that doctors began adhering to more than 2,000 years ago.

“[They] were the original scientific priests, right? … [They] used observation and knowledge to make people better, and that put them in a super powerful part of society, and so doctors decided . . . that that gave them some kind of responsibility. We are the technological priesthood of the 21st century, or perhaps of the third millennium. Everyone here has fixed their family’s computers,” he noted in his talk. “Every time you do that, it reminds you of the incredible complexity of the world that underlies our day-to-day activities and that the majority of people do not understand. And we do. Maybe that gives us moral obligations just like doctors have always had.”

At the end of the talk, he posed a series of hypotheticals in which a security official was being asked to betray his ethical convictions, usually by a corporate superior. One example was: Suppose you find, for instance, a secret “data collection” mechanism in your company’s infrastructure, and your boss orders you to “drop it.”

For each hypothetical he then discussed a series of possible responses. Tellingly, the correct response was never to do as you were told.

Three months later, he became the chief information security officer of Yahoo.

The crumbling aqueducts of Rome

By early 2014 Stamos was a prominent figure in the security community. He was a frequent speaker at conferences, had a growing Twitter following, and was writing an influential blog called Unhandled Exception (meaning a software flaw that’s not fixed).

When Artemis failed to win control of the .secure name, Stamos went looking for a new challenge. He yearned to dirty his hands in the arena.

“Both as a consultant and commentator,” he recalls, “I’d spent years as somebody who just got to complain about other people’s actions. ‘Oh my god, look how these people screwed up. So stupid.’ I did start to realize that just complaining is not, in the long run, helpful. Somebody’s going to have to take responsibility for making the hard calls. One of the reasons I took the Yahoo job was to finally try to see behind the curtain.”

When he joined, in March 2014, some in the security community were surprised to see him take it on. An old infrastructure—Yahoo was founded in 1994—is inherently more difficult to secure, and, at the time, Yahoo’s had been neglected. “I thought of it as the crumbling aqueducts of Rome,” says Moussouris, of Luta Security. “Securing it was going to take years.”

Though Yahoo’s security team had been highly respected in the early-to-mid 2000s—when members were admiringly dubbed The Paranoids—those days were passed. The company had gone through contraction, financial hardship, and turmoil. When Marissa Mayer took over in July 2012, she was the company’s fifth CEO in three years. Early in her tenure, in January 2013, she fired Yahoo’s then-CISO and didn’t replace him for 14 months, until Stamos was hired.

“Not having a CISO at the helm was incredibly detrimental,” a then-member of its security team, Ramses Martinez, would later testify in litigation that arose from the company’s subsequent data breaches. Its security sank to “deplorable” levels during that period, he said. With no one at the helm, the Paranoids shrank in number from 62 to 43, according to figures that later emerged in litigation. (Martinez, who moved to Apple in August 2015, did not return messages.)

In fact, we now know that in August 2013—seventh months before Stamos arrived—the company had been victimized by the largest intrusion ever, with 3 billion accounts compromised. (This was a different intrusion from the earlier-mentioned state-sponsored one in 2014, which is now believed to have involved 500 million accounts.) The attackers responsible for the 2013 hack remain a mystery. The repercussions from the 2013 hack were exacerbated by the fact that personal passwords at the time were then still being encrypted with an outdated technology—an MD5 hash—which was easily cracked using the processing power available in 2013. (The password encryption was improved shortly thereafter. Indeed, all descriptions of Yahoo’s security problems in this article are historical. In the years since the intrusions, numerous security upgrades were instituted by both Yahoo and Verizon Media, whose parent company acquired the company in June 2017.)

Nevertheless, Stamos was also joining Yahoo at a time of optimism. “I joined at what you can call the end of the beginning [of Mayer’s stint at Yahoo],” Stamos says. “Marissa brought all this excitement.”

“Part of my deal was, I would be able to invest in hiring good people,” he continues. And for several months he did.

In September 2014, though, activist investor Starboard Value bought into the company. It demanded that Mayer immediately find a way to monetize value for shareholders. Suddenly everything changed, Stamos says. It became hard to hire, there were stealth layoffs, and he couldn’t use his allocated head count.

In addition, the technical challenges were proving greater than anticipated. “There were parts of the network where nobody knew how it worked anymore,” he says. “Like the people who built the stuff had left or retired.”

Most important, there was no intrusion detection system, which he considered “basic” for protecting a major tech company in 2014. “There was no way to see if anyone had broken into any computers or to track bad guys on the network.”

When he got there, Yahoo was having a big problem with “account takeovers”—situations where spammers would send ads that appeared to come from users’ Yahoo mail accounts. (Stamos now believes these takeovers must have stemmed from the 2013 intrusion.)

“There was statistical evidence that their passwords had been breached,” he recounts. “There was a cliff on this one graph that indicated to us that that was the point at which access to passwords was cut off to the attackers.”

But there was no hard evidence. He says he discussed the matter with general counsel Ron Bell at the time, but because Yahoo invoked attorney-client privilege as to those conversations in later litigation, he declines to relate them.

Unable to invest in a state-of-the-art intrusion detection system, Stamos’s team “kind of MacGyvered together” a substitute, he says. Using that they poked around the network to see if any attackers had exploited an industry-wide software bug of the time, called Shellshock. They found something weird.

By October 9 the incident response team, led by Martinez, identified the issue. There were hackers in the system. They had located and attacked Yahoo’s Account Management Tool, and were using it to stage surgical raids on the email accounts of specific targets—Russian journalists, Russian government officials, Russian industrialists, and so on. The team code-named the attack “Siberia.”

By November at least 26 accounts had been compromised, in addition to CEO Mayer’s and Stamos’s. Yahoo notified the FBI and, in December, the 26 victims, but there was no wider disclosure. The security team gave numerous debriefings during this period to senior Yahoo officials, which no one contests.

Meanwhile, Stamos’s team was fighting to get the hackers out. “I feel like the work to investigate and stop the breach was probably some of the best work I’ve done in my career,” he says. “Because we were handed a network that had none of the standard protections that you would expect in a production-level network in 2014. Some of the [internal server] passwords had not been changed in 15 years. There was this thing called the Filo password [after Yahoo co-founder David Filo] that the hackers got, which was a backdoor password to enter every single server. There was no network flow data available. The configuration management was horrible.

“To get them off the network,” he continues, “we had to change massive parts of the network while it was running. Over one weekend in December we finally were able to put all of these things in place and completely change fundamental parts of how Yahoo worked. I thought there was a decent chance we were going to bring all of Yahoo down doing that, and we didn’t. So I’m proud of the team.”

The big exfiltration, Aleksey Belan, and 30 million forged cookies

On Wednesday, December 10, 2014, however, a crucial event occurred that altered the gravity of the event. This is the event that Mayer and some other senior officials have claimed they were not told about until two years later, after Stamos was gone. The Paranoids discovered that in early November the attackers had copied and transferred (“exfiltrated”) to a server outside Yahoo at least a portion of a backup user database (UDB) storing vast quantities of users’ personal information.

That same day, at 5:03 p.m., Stamos emailed an “incident presentation” to five Yahoo in-house lawyers, including general counsel Bell, according to an email later produced in litigation. The full presentation—a slide deck prepared by incident response chief Martinez—is still under protective order. But excerpts quoted in unredacted filings are clear and blunt: “best case scenario is 108M [million] credentials in UDB compromised, and worst case scenario is all credentials in UDB compromised.”

Stamos, who had been trying to schedule a face-to-face meeting with Mayer about the intrusion for more than a month, finally met with her the following evening, according to contemporaneous email traffic. After the meeting he emailed general counsel Bell—who was out of town—to arrange a call to fill him in and talk about next steps. Bell promised to call him as soon as he reached San Francisco.

Stamos says there were a lot of briefings, and he can’t remember the specifics of any particular conversation. (He and Martinez also briefed the Yahoo board’s audit committee on the intrusion in April and June, according to minutes that relate no details.)

Stamos says that senior management, including Mayer, “knew everything we knew. We were not hiding anything.” Martinez’s testimony was to the same effect.

Yahoo made no public disclosure of the mammoth exfiltration, nor did it require users (other than the 26 known targets) to change passwords.

“I disagreed with it,” says Stamos, “but it was not my decision. And I didn’t set myself on fire over it. I considered it my job to actually beat the bad guys.”

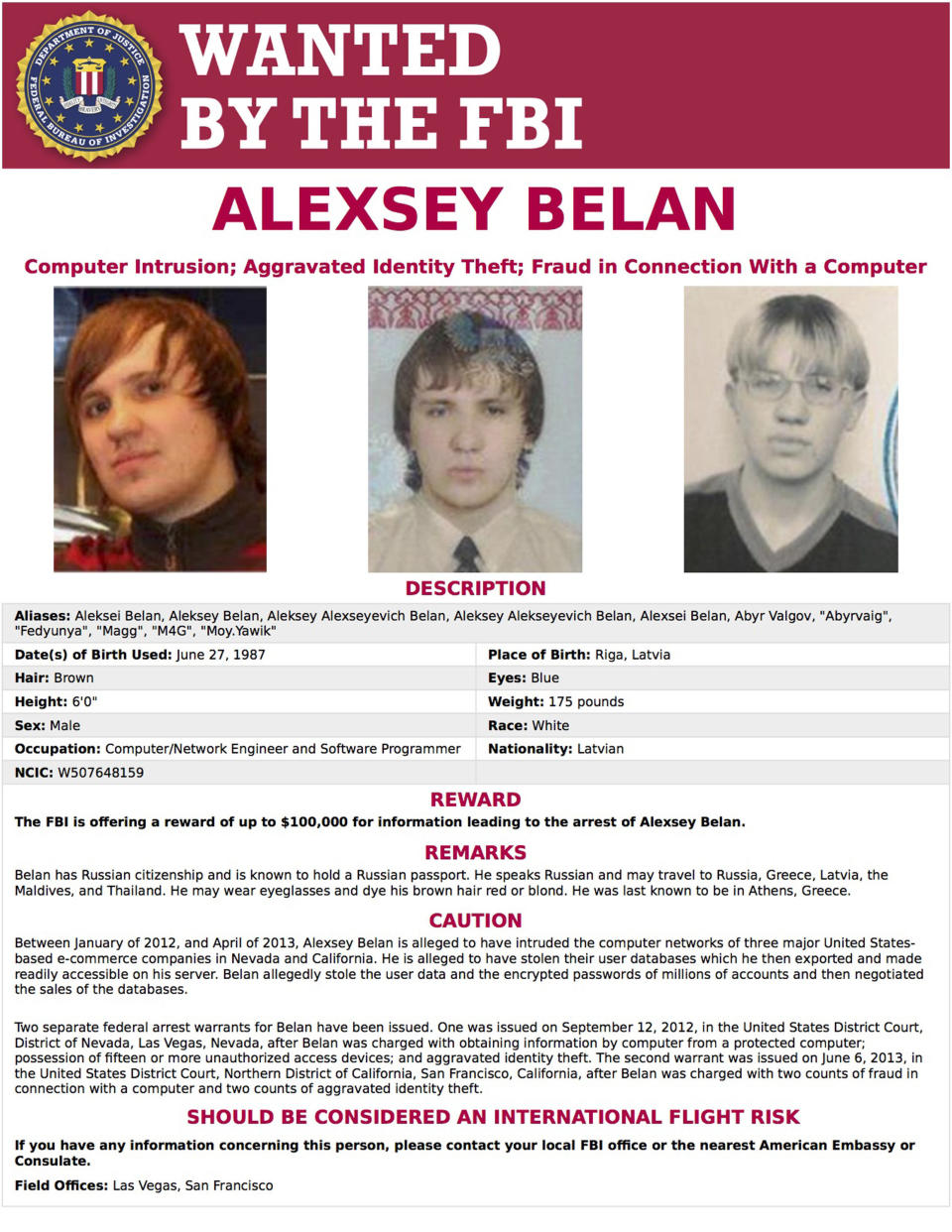

Despite his team’s best efforts, we now know that he did not succeed in chasing the hackers off the Yahoo network. According to a federal indictment unsealed in March 2018—the “attackers” were actually one very skilled individual: Alexsey Belan, then 27. Born in Riga, Latvia, and a Russian citizen, he had already been indicted twice in absentia in the United States for earlier e-commerce intrusions. He had been on the FBI’s “most wanted” list of hackers and the subject of an Interpol Red Notice since 2012.

Belan was acting on the orders of two officers of the Russian FSB (Federal Security Service), a successor to the Soviet KGB. At the same time, according to the indictment, the FSB appears to have been allowing Belan to compensate himself for his intelligence work by also pillaging Yahoo’s network for personal gain, through assorted digital mayhem, including credit card theft, spamming schemes, and diverting searches to spoof sites.

In April 2015, Belan—using “log cleaner” software to cover his tracks—returned to the network to raid several accounts targeted by the FSB, while also shopping for credit card numbers from others. In June, the month Stamos left Yahoo for Facebook, Belan installed a malicious script on the network that could mint, or forge, “cookies” in bulk, which he then exfiltrated outside the company. With the cookies—software installed on a user’s browser that indicates someone has visited a site previously—he could stealthily enter targeted accounts without a password. In July, he made 17,000 such cookies, and showed his FSB handler how to use them. In August he stole and exfiltrated Yahoo’s source code for making cookies, enabling him and the FSB to mint cookies off site. Eventually they forged 30 million of them. (The cookies replied on cryptographic data in the exfiltrated user database. Had passwords been changed, the cookies would not have worked, according to the indictment.)

Using cookies, Belan continued breaking into the accounts of dozens of FSB targets—an investigative reporter for Kommersant Daily, an International Monetary Fund official, a Nevada gaming official—through October 2016, a month after Yahoo disclosed the 2014 intrusion.

Often when Belan broke into a Yahoo account he would find information relating to the users’ other online accounts. The FSB hired a second hacker, a Canadian national named Karim Baratov, to use that information to break into the target’s other accounts—mostly gmail. Baratov was arrested in Canada in March 2018, extradited to the U.S., and is now serving a five-year prison term. Belan is still at large.

Yahoo disclosed the 2014 breach in September 2016 and the 2013 breach in December 2016. (The company had been tipped off by law enforcement, after data from hundreds of millions of accounts was offered for sale on the Darknet.) The SEC fined Yahoo $35 million in April 2018 for not disclosing the 2014 breach earlier, and Yahoo is still in negotiations to settle the last of the resulting class actions, which have already cost it more than $80 million. Yahoo’s then-general counsel, Bell, resigned in March 2017 with no severance, losing millions. The board denied then-CEO Mayer a cash bonus, worth up to $2 million, and she voluntarily agreed to forego a 2017 equity award, reportedly worth $12 million. Mayer and Bell did not return multiple emails, and an attorney for Bell declined comment.

The kernel module

In early 2015, less than a year into his stint, Stamos was becoming frustrated at Yahoo. He had still not been able to get an intrusion detection system.

In February, he fired off an email to his boss, Jay Rossiter, the company’s then-senior vice president for science and technology. He complained that he’d lost seven people—11% of his headcount—due to belt-tightening. These cuts left his team “well below …the minimum staffing necessary to protect Yahoo in the current threat environment,” he warned in the email, which surfaced in the litigation. “We will need to begin passing on future product and vendor security reviews with ‘Paranoids cannot review, please have your L2 accept the risk.’” L2s were the top officials who answered directly to Mayer—like Rossiter. (Rossiter could not be reached for comment.)

At about that time, Stamos says, Facebook’s chief security officer, Joe Sullivan, asked him to lunch. Sullivan knew him from when he did consulting work for Facebook while still at iSEC. Sullivan told him he was leaving to take another job, and suggested he apply for his Facebook position. Stamos did have some exploratory discussions, he says, but he wasn’t yet ready to jump.

The last straw came in May, he says. His team found what he calls a “kernel module,” or “rootkit,” on the Yahoo mail servers—software that provides access to the computer in a hidden manner. “Initially, we thought the Russians had come back.”

He discovered, however, that the device had been placed there by engineers in the mail unit who were apparently complying with a court surveillance order. The device was searching for a particular character string in emails, according to a later Reuters account.

Stamos was furious this had been done behind his back. He asserts that the engineers did it in a way that “created a security vulnerability.” He suspects he was kept out of the loop because managers feared he would urge them to fight the surveillance order.

“My understanding is that it was an intentional decision,” he says. “That Marissa made that decision.”

On the other hand, one person familiar with the situation provides Yahoo’s perspective. Yahoo was always diligent about protecting its users’ privacy, this person maintains. In this particular instance, however, not only did legal requirements seem to be met, but the company was led to believe that the request was uniquely urgent and important. Complying was straightforward, and was handled by the team that always handled such issues, the person asserts.

In any case, Stamos gave 30 days notice.

“It was like, really?” he recounts. “How can I do this if you don’t trust me enough? I wasn’t making things better. I wasn’t getting anything approved. They were actively making the systems worse without telling me. A backdoor! What’s my point to being here?” (Verizon Media declined comment.)

He left Yahoo in June and started at Facebook the same month.

“The most important company in the world”

Notwithstanding Stamos’s fury at Yahoo, the breadth of his experience grew greatly while there. The White House National Security Council and its Office of Science and Technology periodically consulted with him on infrastructure and encryption issues, according to people who served on those bodies. He worked with law enforcement to combat abuses of the technology that were not narrowly cyber at all: child sexual abuse rings, fraud, kidnappings.

Lay people began to hear about him. In February 2015, he had a live-streamed confrontation with the then-NSA Director, Adm. Michael Rogers, at a security conference in Washington, DC. Rogers was calling for tech companies to build backdoors into encrypted products to permit U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies to penetrate communications between consumers.

“So it sounds like you agree with [then-FBI] Director [James] Comey that we should be building defects into the encryption in our products so that the U.S. government can decrypt—,” Stamos began.

“So that would be your characterization, not mine,” Rogers responded.

“Well, I think … all of the best public cryptographers in the world would agree that you can’t really build backdoors in crypto,” Stamos pressed. “That it’s like drilling a hole in a windshield.”

The tense back-and-forth, which lasted several minutes, was not just cheered on by the tech press—“Yahoo exec goes mano a mano with NSA director”—but drew coverage in the Washington Post, the BBC, and CNBC.

Upon moving to Facebook, his portfolio and visibility would each expand by another factor of 10.

“It was perhaps the most important company on the planet,” Stamos says.

He felt the increased scrutiny immediately. Within two weeks of arriving, he flew into a rage one Sunday morning when his team told him that a flaw in Adobe’s Flash software—widely used on Facebook for social games—was being exploited by malicious actors in China to threaten students in Hong Kong.

Characteristically, he dashed off an angry tweet: “It’s time for Adobe to announce the end-of-life date for Flash.” But this time his fit of pique generated headlines in tech publications: Facebook’s CSO wanted to kill a leading software product.

“The CEO of Adobe actually called executives at Facebook to complain,” Stamos recalls. “They were supportive of my position, but also asked me to be more careful.” (Adobe did not respond to inquiries.)

Then came the 2016 presidential election. It placed Stamos in a spotlight the likes of which no other infosec guy had ever found himself before.

Candidate Donald Trump was not just a master of social media, but someone many saw as its demonic embodiment. Social media metrics craved and rewarded exactly what Trump dished out. Its algorithms sought engagement above all, which happened to be driven by sensation, outrage, provocation, hate, anger, and lies. When he was elected president of the United States by a razor thin margin, the vanquished wondered: Was it coincidence that just as social media was coming of age, this politically inexperienced reality TV star had pulled off the electoral upset of the century?

Facebook came under wave after wave of scrutiny, as people blamed it for Trump’s victory. Its algorithms had caused filter bubbles, they theorized. Its failure to protect user data privacy had allowed Republican Super PACs, through Cambridge Analytica, to hypertarget key voters with misleading campaign ads. Its negligence had allowed Russian intelligence agents and internet trolls to run riot across its platform.

As Facebook’s chief security officer, Stamos was presumed involved, if not guilty. (He actually had nothing to do with its algorithms, or with its evolving data privacy policies, which spawned the Cambridge Analytica controversy.)

“It’s an interesting question,” muses professor Persily, the head of Stanford’s Project on Democracy, “whether, if Hillary Clinton had won, we would have had these years of national and international criticism of the social media platforms and, particularly, Facebook.”

More Russians: the GRU

For Stamos, the world began changing in spring 2016, when a Russia specialist working under him raised a warning. As first reported by The New York Times, he told Stamos that people he believed were Russian government agents were looking at the Facebook accounts of officials involved in the U.S. presidential campaign. They weren’t doing anything illegal, or even violating Facebook’s terms of service (TOS) at the time, but it might have been the type of reconnaissance that could precede a cyber attack.

Facebook notified the FBI, but did not close the accounts.

We now know that in March 2016, two units of the GRU, the Russian military’s Main Intelligence Directorate, launched a spear-phishing campaign aimed at volunteers and employees of the Democratic National Committee, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, and the Hillary Clinton campaign. They were, according to an indictment obtained by Special Counsel Robert Mueller III in July 2018, tricking people into surrendering their password credentials, which could then be used to pry inside their employers’ networks.

On March 21, GRU officers stole 50,000 emails from the account of Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta. In April they penetrated the DNC network, eventually gaining control of 33 of its servers. In late May they stole thousands of DNC emails.

On June 8, purporting to be “American hacktivists,” they launched the website DCLeaks.com. That same day they also set up a DCLeaks Facebook page (and opened an @dcleaks Twitter account).

Soon, the GRU began leaking some of the stolen emails from the DCLeaks.com site. The intelligence officers used the affiliated Facebook page, registered in the phony name of Alice Donovan, to send readers to the leak site. They also set up other fake accounts, using names like Jason Scott and Richard Gingrey, to do the same.

On June 14, the Washington Post reported that the DNC had been hacked by agents of the Russian government—the conclusion reached by the DNC’s consulting firm, CrowdStrike. (For those keeping score on a different developing story, that happens to be the same day that Michael Cohen, personal attorney to candidate Donald Trump, told hotel developer Felix Sater that he, Cohen, would not be going forward with a trip to Russia they’d been planning for months. The trip related to plans to build a Trump Tower in Moscow.)

By August another security boutique had specifically identified DCLeaks as a Russian front. But Facebook still didn’t close the account immediately, because it wasn’t violating Facebook’s TOS of the time.

“This was a big internal argument,” Stamos says. “But in the end it didn’t really matter.”

What he means is this. After the CrowdStrike report, the GRU created a persona, dubbed Guccifer 2.0, to contest its conclusion. Claiming to be a lone hacker from Romania, the Guccifer 2.0 persona then reached out to reporters (and to recently indicted Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone) to tell them where to look for damning emails—like those, for instance, suggesting that top Democratic campaign officials had played dirty to undermine Bernie Sanders’s primary bid. Wikileaks soon contacted Guccifer 2.0, offering the use of its more renowned conduit for leaking the contraband.

“So once they got this stuff in the hands of Politico and The Hill and others,” says Stamos, “those guys wrote the first stories, and then The New York Times, Washington Post, and others amplified it, and with 24-hour cable news, whether we took down their Facebook accounts or not didn’t matter.”

Stamos put it more truculently in a tweet last November: “The mass media was completely played by the GRU and wrote the stories they wanted…. You could argue that this was much more impactful than the IRA disinfo, and there has been almost no self-reflection by NYT/WaPo/WSJ/TV on their role.”

(Eventually, in October 2016, after the GRU officers did post some stolen emails on the DCLeaks Facebook page—a violation of the TOS—Facebook removed the account.)

And still more Russians: the IRA

We also now know that there were still other Russians exploiting Facebook during the run-up to the election. As early as April 2014—when Stamos was still at Yahoo—the Internet Research Agency, a Kremlin-supported troll farm based in St. Petersburg, began preparing to interfere in the 2016 elections, according to yet another Mueller indictment unveiled in February 2018.

By September 2015, three months after Stamos got to Facebook, the IRA began placing videos on YouTube, a Google unit, as part of its political influence campaigns, eventually producing 1,107 of them across 17 channels. By early 2016 its members, pretending to Americans, were creating individual and group Facebook pages under names like “Secured Borders,” “Blacktivist,” “United Muslims of America,” and “Heart of Texas.” (They were opening similar accounts on other social media, including Facebook’s Instagram, Twitter, Reddit, Yahoo’s Tumblr, and Pinterest.) The messages were mainly geared to promote the Trump campaign, but some also supported Bernie Sanders. After Sanders lost the nomination, IRA accounts also lent some support to vote-draining, third-party candidate Jill Stein, while the agency’s phony Black and Muslim groups urged their followers not to vote at all. (The most recent reports on IRA activity, published in mid-December by contractors hired by the Senate Intelligence Committee, found that in 2017, as Facebook drew scrutiny, the IRA switched its activity to Instagram, and that misinformation on Instagram may have had wider reach than on Facebook.)

If U.S. government authorities knew anything about this influence operation at the time, they weren’t sharing it with social media companies. And such campaigns weren’t on anyone’s radar at Facebook.

“My responsibility was either governments hacking Facebook or using Facebook to hack others,” says Stamos.

Ashkan Soltani, a former chief technologist for the Federal Trade Commission and White House adviser, says the whole security community was slow to anticipate this sort of assault. “We’ve done a decent job at foreseeing platform abuse,” he says, “but only in terms of hackers getting on our system to take our data. We haven’t thought so much about how they might get on our systems to hurt people outside of our networks. These people wanted to use our tools to hurt society.”

“They were using technology as it was technically designed to be used, but not as it was philosophically designed to be used,” says Moussouris, of Luta Security. “It’s impossible for technical people to design a philosophically abuse-proof system.”

Three days after the election, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg made a now-infamous impromptu statement at a conference: “Personally I think the idea that fake news on Facebook … influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea.” (He later apologized.)

“It was clear to me [then],” Stamos says, “that he had not been getting briefed on anything we were finding.”

His team wrote up a memo about what it knew at the time about Russian activity—mainly the GRU activity—which was presented to Zuckerberg and COO Sandberg in December. (The Times has reported that Sandberg was angry that Stamos drew up this report without being asked. Stamos says she never expressed anger to him, but doesn’t know if she expressed it to others.)

Zuckerberg then ordered the products team to conduct a quantitative evaluation of fake accounts and “fake news” on the site—a nebulous term at the time. By January, this effort, known as Project P (for propaganda), had found that the vast majority of fake news was actually financially motivated. Facebook took steps to stanch this activity—disabling inauthentic accounts.

While Project P was occurring, and in parallel with it, Stamos was becoming aware of Russian (and possibly Iranian) influence operations—coordinated political activity by inauthentic accounts—on the site.

On January 6, 2017, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence—amalgamating the joint assessments of the FBI, CIA and NSA—issued a report concluding that “Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the U.S. presidential election” and that “Putin and the Russian government developed a clear preference for President-elect Trump.” The report mentioned not just the GRU hack-and-leak campaign, but also the Kremlin’s use of “paid social media users, or ‘trolls.’” With one exception, however, the report never singled out Facebook by name. (The exception was a reference to the fact that the Kremlin-funded quasi-news organization RT America TV had created a Facebook app to connect Occupy Wall Street protesters during the run-up to the 2012 US election.)

Stamos decided to have his team write a white-paper about the influence operations on Facebook.

“He’s an envelope-pusher, and that was an envelope pushing thing to do,” says one person who worked with him at the time. “Trying to get it out the door was a Herculean feat.”

Facebook’s legal team, policy team, and communications team—all risk-averse—had to sign off. “We had like 80 or 90 drafts,” says Stamos. The main thing that was taken out were examples of such posts, which the legal team feared would violate various privacy laws or decrees. Weirdly, he says, the Russians—even though they were lying about their identities—were considered customers of Facebook Ireland, and covered by strong privacy laws.

Notoriously, Stamos’s final report, which came out April 27, 2017, never used the word “Russia.” Instead, it said its data did “not contradict” the DNI report, to which it linked in a footnote.

“While I lost that battle,” Stamos says, “in the end I agreed to the compromise.” Otherwise, he notes, “we were going to be the second organization on the planet to say the Russians helped Trump. And you have to be an idiot to read this and not see that we’re saying Russia. Without creating the situation where people will be able to directly quote us and turn that into the headline.”

There were still shoes to drop. Congress was asking Facebook for information on the Russians’ use of ads. The company performed another massive quantitative analysis. Stamos then authored a post summarizing its findings, which emerged on September 6, 2017. This one revealed that Russians, acting through 470 “inauthentic accounts,” had spent $100,000 on about 3,000 political ads between June 2015 and May 2017.

It was while debriefing Facebook’s audit committee on this impending post that committee member and former White House chief of staff Erskine Bowles became enraged, according to the Times report that came out 14 months later. The day after the Bowles debriefing, according to the same article, was when COO Sandberg accused Stamos of “throwing [her and Zuckerberg] under the bus.”

Hypertargeting and “one-hundred-million-faced” politicians

The most disturbing statistic was yet to come. General counsel Colin Stretch revealed it in testimony before a Senate committee on October 31, 2017. The company estimated that about 126 million people—about 40% of the U.S. population—had been shown at least one piece of IRA-generated content between January 2015 and August 2017.

At the same time, though, Stretch said that the total number of stories Americans were exposed to in their newsfeeds during that period was about 33 trillion. So the Russian content accounted for about “four-thousandths of one percent,” he testified.

If so, was Zuckerberg’s notorious, now retracted, statement—that the notion that fake news could have swung the election was a “pretty crazy idea”—actually right?

“People are writing books right now about whether the overall Russian activity affected the election,” Stamos says. “We might never know. Quantitatively, the direct Russian activity is still quite small. Even with everything we know now.”

The more important issue, he believes—and this is characteristic of Stamos’s views on a host of Facebook controversies—is one that neither the press nor Congress is adequately focusing on.

“Almost certainly the thing on Facebook that was most impactful in the election was the fact that the Trump campaign and the Republican PACs were so much better at Facebook ads than the Democratic side. You’re talking about well over 100 times more dollars spent than the Russians did, and not quite twice what the Democrats did.”

“The Russian stuff was not that advanced,” he continues. In contrast, “the Trump campaign was generating thousands of ads programmatically. They were testing those ads against hundreds of different segments of the population. They were automatically, then, saying, this one tested well, we’ll put our money behind it.”

This “hypertargeting” of ads is “negative for our democracy,” he asserts. “Imagine you could afford to send a mailer to every single voter in the country and every single one of them is different. You’re not two-faced; you’re one-hundred-million-faced. I wish people had access to the entire database of Trump ads and Hillary ads and all the targeting data.”

But due to various privacy laws, he says, Facebook can’t currently make that data available. Congress should demand it, he proposes, via subpoena or legislation.

He’s also frustrated by the media’s continuing focus on Cambridge Analytica. “They talk about the 50 million [Facebook] profiles that were viewed by [academic Aleksandr Kogan and later passed on to Cambridge Analytica]. The problem is not that he was able to get this data in 2014. It is that today there are twenty Cambridge Analyticas that still exist. They’re just not dumb enough to steal data from Facebook. They legally buy it from Equifax and Transunion and Acxiom and all these different data brokers. And Facebook and Google create an ecosystem for those to exist by allowing them to then hypertarget ads.”

The reorganization

About three weeks after Stretch testified before Congress, Stamos decided to address a long-festering issue he had relating to lines of reporting at Facebook. In some respects, it was an issue that’s bothered him his whole career.

Throughout the industry, Stamos contends, security teams are often brought in too late in the game. The goal of people who design products, he says, “is to make something that people love and that eventually makes money. … These product visionaries come up with these big decisions, and then push the responsibility to make it safe and secure to other folks. … But the actual responsibility has to be there when you’re making the big design decisions.”

At a more micro-level, Facebook had some organizational issues specific to it. When Stamos arrived, there were two silos of security—one in the engineering department, which ultimately answered to Zuckerberg, and a separate one, which he was hired to run, which answered to general counsel Stretch, who answered to Sandberg.

Stamos wanted to merge the two groups, and have them answer to a vice president of product—closer to the decision-making process—who would then answer to Zuckerberg, he says. He submitted a proposal around Thanksgiving. He imagined that he might be kicking off a six-month, back-and-forth process, with multiple meetings that Stamos would be participating in.

Instead, the decision came back about two weeks later, fait accompli. A variant of his proposal had been accepted, but without him in the picture. He could keep his CSO title (and comp package) and continue to do public policy work, or he could do security for Oculus’s augmented reality/virtual reality project, or some other alternatives.

Stamos suspects the putsch was payback for having alienated people shortly after he arrived at the company, he says. Back then he’d done a blunt assessment of the company’s then-security needs—what was good, what was bad—and had stepped on toes.

After the reorg, Stamos helped with the transition and worked on security for the upcoming midterm elections while he looked for a new position.

“I had a couple job offers for CISO jobs,” he says, “but I wanted to work on bigger picture issues.”

The challenge of our age

At Stanford, he is certainly working on big picture issues. His vision for his Stanford Internet Observatory is so ambitious that it might well prove unworkable. “Our goal is to perform a multi-year study across multiple platforms and types of communication networks, to really understand how these attacks on democracy can be stopped,” he says.

The hurdle is: How will academic researchers ever gain access to the mammoth databases of sensitive, private, social media data in our post-Cambridge Analytica world? Remember, that scandal occurred because an academic allegedly misused data he got from Facebook for research purposes.

Last July, a nonprofit called Social Science One was set up to provide “privacy protected access” to data that Facebook committed to making available last April. SSO’s long-term vision is to persuade Google, Twitter, and other social media companies to offer access to their data, too.

“You’re talking about tens of petabytes of data,” says Stamos, for the Facebook data alone. “To store that you need something like 1,000 computers. You’re going to have to come up with a model where academics can do the research and the data stays within the companies.”

SSO is funded by seven big nonprofits, works in conjunction with the Social Science Research Council, and is under the supervision of two professors, Harvard’s Gary King and Stanford’s Persily.

“This is the challenge of our age,” Persily says. “It’s really unique in human history that these private companies have so much private data on social interaction that is out of reach of academics that might try to study it, or of governments that might try to use it to enforce the law.”

So far, Persily admits, the process has been frustrating. In a recent update on SSO’s blog, he says that progress has been bogged down by “legal, technical, organizational, computational, privacy, and security challenges.”

“We haven’t met our goals,” he says in an interview. “But we’re trying to build the space shuttle here. If we do it right, the payoff will be great.”

Meanwhile, Stamos says he’s happy at Stanford. In his spacious, naturally lit kitchen he certainly looks relaxed and content as he strokes his goldendoodle, which has climbed up on the counter where she’s not supposed to be. Then Stamos’s face suddenly seizes up as he remembers a presentation he gave at Facebook in fall 2017 about the Russian election activity. After that meeting, he recalls, a colleague came up to him and said: “The look on your face is the look I had before I had my first heart attack.”

Stamos says he doesn’t want another job like that one. But several years down the road, he admits, he might consider an “impactful” job in government.

The gravitational pull of the arena—where the white hats perpetually face off against the black hats—is palpable.

Correction: This article originally stated that SSO was supervised by two Stanford professors. In fact, it’s supervised by a Harvard professor and a Stanford professor. The error has been corrected.

Roger Parloff is a former editor-at-large at Fortune Magazine, and has been published in Yahoo Finance, Yahoo News, The New York Times, ProPublica, New York Magazine, and NewYorker.com, among others.