How to help Trump win his trade wars

Want to help President Trump achieve his biggest goal on trade? Well, you can, by doing one simple thing: buy less and save more.

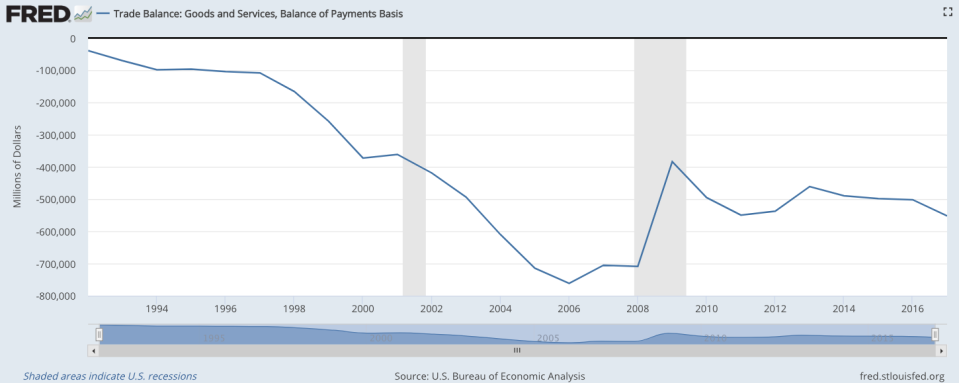

One of Trump’s top priorities is reducing the U.S. trade deficit, which was $552 billion last year. Trump has singled out China in particular, since that one country accounts for the bulk of America’s trade deficit with the world. In 2017, Americans bought $524 billion worth of Chinese stuff, while the Chinese bought only $188 billion worth of American goods and services. So the U.S. trade deficit with China was $336 billion.

Most economists say there’s nothing inherently wrong with a trade deficit. Americans pay dollars for stuff they want, and foreigners get dollars that they must invest somewhere—often, in U.S. assets like Treasury or corporate securities. But Trump sees it differently, and has made it a priority to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with China and other countries.

“We benefit from trade,” says economist Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute, a former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund. “The problem is there are people around Trump telling him that trade is a zero-sum game, that if you win, someone else loses.”

[Check out our Trump trade war scorecard.]

That’s why Trump has imposed tariffs on about $52 billion worth of Chinese imports, and threatened further tariffs on another $400 billion worth of Chinese stuff. Trump thinks taxing Chinese imports, and making them more expensive, will force Americans to buy more American-made merchandise and lure more producers to the United States. But that’s not the way trade works. “He is unlikely to achieve any of these objectives,” Dartmouth economist Douglas A. Irwin wrote recently. “His policies will likely be an exercise in frustration.”

There are ways to reduce the trade deficit, it turns out. But Trump isn’t pursuing them. The trade deficit exists because America as a whole spends more than it produces, and must therefore buy foreign products to meet domestic demand. Trade is complicated, but in general, countries with relatively low savings rates tend to have large trade deficits, while countries that save a lot—such as China, Germany and Japan—have surpluses.

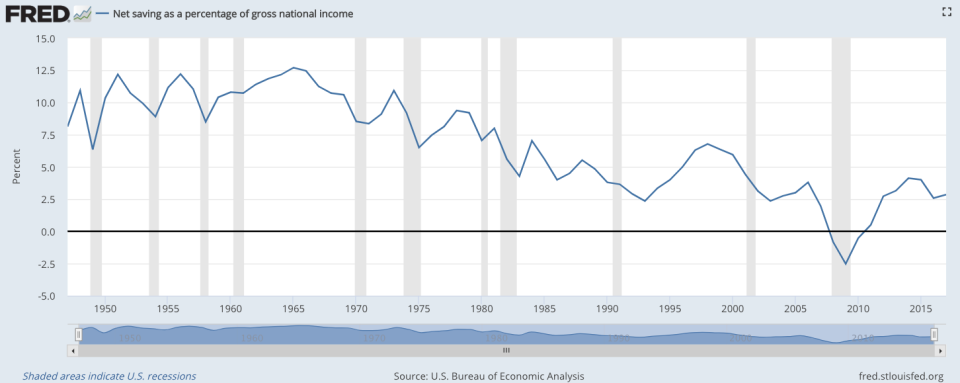

As the following two charts show, the net savings rate in the United States has been on a downward trend since the mid-1960s, while the trade deficit has been generally rising. (Trade data are only available going back to 1992.)

National savings consists of three sectors: government, business and household. The federal government has been running annual deficits since 2002, and the Trump tax cuts that went into effect this year are pushing the annual shortfall close to $1 trillion per year. So U.S. government savings is solidly negative.

Business saving is a net positive, but it’s been declining since 2010, even as corporate profitability has steadily improved. And personal saving in the United States is low, with Americans banking just 6.4% of after-tax disposable income.

In a consumption-based economy such as America’s, less buying and more saving might sound like a bad thing. But saved money typically becomes investment, which generates economic activity, and, if done right, nets a positive return that helps build wealth. China, by contrast, has one of the highest savings rates in the world, in part because there are minimal safety-net benefits such as Social Security and Medicare. So the Chinese sock money away to pay for their own retirement needs—and buy relatively few foreign products. The International Monetary Fund has actually lobbied China to implement policies that would reduce savings and boost consumption, to even out imbalances such as its huge trade surplus with the rest of the world.

Trump’s policies, ironically, may actually push the trade deficit higher, since the tax cuts and spending increases he signed will add substantially to deficits and push national saving lower still. “What Trump’s doing is just crazy,” says Lachman. “If he’s serious about wanting to reduce the trade deficit, he can’t then go and increase the budget deficit, because that’s reducing savings, which is going to increase our trade deficit. It’s just not going to work.” Trump’s not hearing it.

Confidential tip line: [email protected]. Click here to get Rick’s stories by email.

Read more:

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including “Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success.” Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn