Why a tax holiday for the $2.4 trillion held overseas would flop

US business activity has been less than stellar, and politicians agree that one remedy for this is corporate tax reform.

One particular idea that’s been floated is a tax holiday for repatriated overseas earnings. You see, America’s biggest companies consist of multi-national corporations that do tons of business outside of the United States. S&P 500 (^GSPC) generate about 44% of sales abroad. And these 500 companies are holding about $2.4 trillion of those earnings outside of the US, according to Goldman Sachs.

While much of these earnings will continue to finance overseas operations, there is a belief that the existing 35% repatriation tax is preventing companies from bringing that cash back to the US where it could serve some sort of stimulative and productive purpose.

The last repatriation tax holiday boosted share buybacks

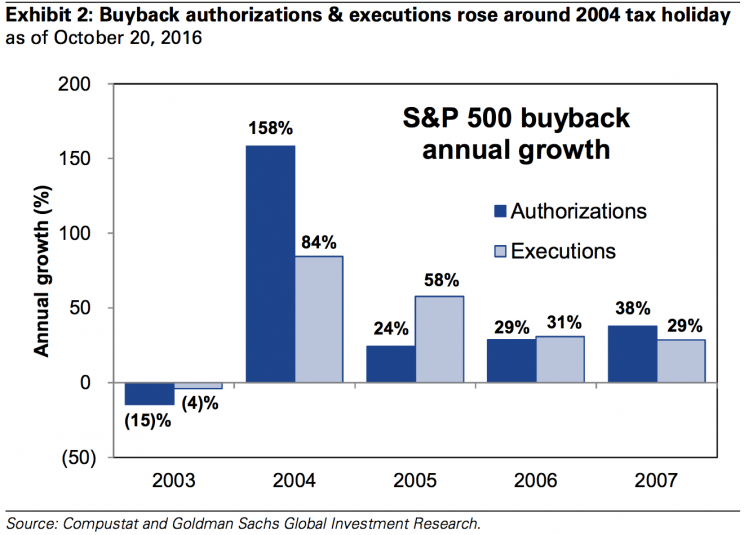

“Historical experience suggests a tax holiday will spur firms to repatriate overseas earnings,” Goldman Sachs’ David Kostin observed. “The Homeland Investment Act (HIA) of 2004 created a repatriation ‘tax holiday’ with an effective rate of 5.25% instead of 35%. Repatriated earnings soared by 270% to $300 billion in 2005 from $82 billion in 2004.”

Unfortunately, this repatriated money wasn’t exactly used as intended. Evidence suggests that instead of sparking a business investment boom, much of this cash was deployed in the form of stock buybacks.

“Despite an explicit prohibition against using repatriated funds for buybacks, it appears that share repurchases benefited from the tax holiday,” Kostin observed. “S&P 500 buyback executions rose by 84% in 2004 and 58% in 2005. The increase in buyback executions was also accompanied by growth in buyback announcements.”

Buybacks have become the most controversial use of excess cash as 1) they aren’t as productive as business investment and 2) they inflate earnings per share by reducing share count.

How does this happen with no one getting punished? Well, this has to do with how cash works. For example, let’s say I’m skirting by in life with a life savings of $1,000. My parents see my unfortunate situation and give me a check for $1,000, and they tell me to hang on to it in case of emergency. Immediately, I go out and squander $1,000 on a night on the town. My parents find out about this and scold me for spending money intended for emergency purposes. I tell them to relax, because “their” $1,000 is still in the bank; I spent a different $1,000 I had.

Kostin cited a study that estimated 60% to 92% of the money repatriated in 2004 went toward share purchases. In other words, the whole project was an epic failure.

He also observed that cash dividends jumped and M&A activity increased in the wake of this tax holiday.

With growth prospects just as lackluster as ever, there’s not much reason to believe that another repatriation tax holiday would work this time around. In fact, data shows that companies continue to be inclined to buy back their shares.

And so while a repatriation tax holiday might be well-intended, it’s clear that companies won’t invest in their businesses until that risk is more attractive than just shoveling cash back to shareholders in the forms of buybacks and dividends.

–

Sam Ro is managing editor at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

The most controversial use of corporate cash could hit $1 trillion this year

A growing chorus of strategists are sounding the same warning about 2017

The next selloff could be triggered by something we’re not discussing right now