Jeffrey Gundlach extended conversation with Yahoo Finance [Transcript]

Following a live hit on Yahoo Finance’s The Final Round (transcript and video here), our conversation with bond king Jeffrey Gundlach continued. He spoke about the outlook for the market, cannabis, Facebook, art, recruiting talent, how he finds market-beating trades, and the 2020 presidential election among other things.

Below is the transcript of our extended conversation.

————————————

Millennials finally believe they got screwed by the system

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I think what's happening is, at long last, the millennials are starting to hate the baby boomers. I mean, that's starting to pull pretty strongly, and it's about time.

I mean, the policies of the United States have been so bad for so long. I think it was seven or eight years ago, I read an article, it was with Esquire, that we're really railing against how much money we spend on old people in the United States government system, as opposed to how much we spend on young people. And in that article the ratio was 7 to 1, how much of the budget goes to paying for things for people over 65 compared to paying for things for people under 21-- I can't remember if it's 21 or 25, whatever-- but young people.

And if you're investing in dying people and not investing in the future, you don't have a very bright future. And so millennials are starting to understand that the baby boomers have all the wealth, and millennials don't, really. I mean, they can't afford a house. They've got student loan debt. They've start to believe, I think, finally, that they kind of got screwed by the system.

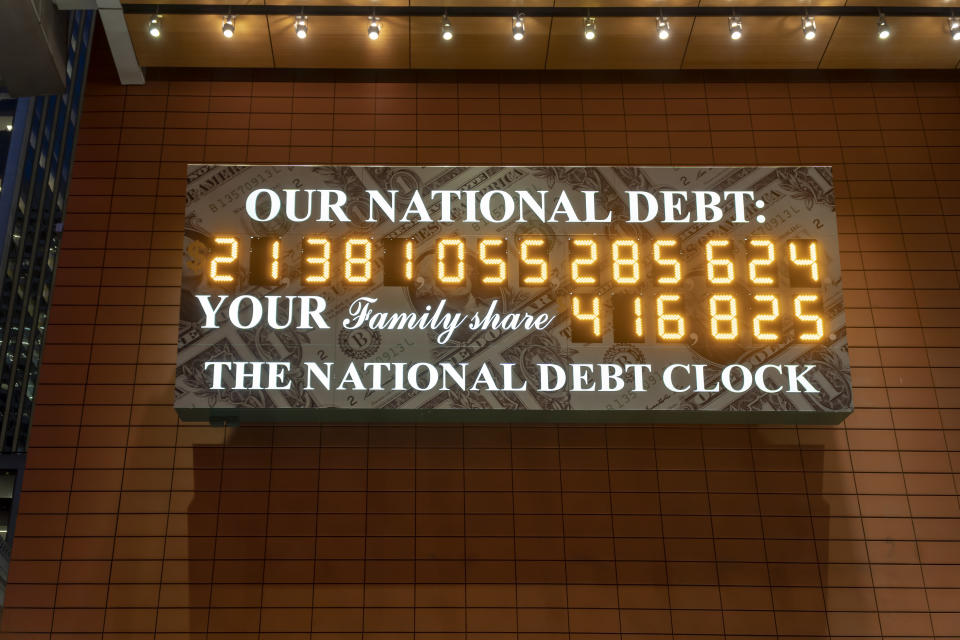

National debt nears tipping point — here’s what has to happen

JULIA LA ROCHE: When you see a number like $22 trillion for the nation's debt, are we past the point of no return? What does the day of reckoning look like?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I think we are really at that tipping point. And so since we're not going to do anything about it in the next couple of years, almost certainly, I think once we get to 2020, 2021, I think you will be past the point of no return. And so you're just going to have to deal with it.

And the problem is that we have $22 trillion in debt, and it's growing very rapidly, but we also have $123 trillion in unfunded liabilities. The state and local pension systems in the United States, on average, are 50% underfunded. So if you take a look at Illinois, there's no chance that Illinois can honor its pension obligations to its public unions. It cannot do it.

So what's the solution? The solution is, you have to cut benefits. When you have $123 trillion of unfunded liabilities, you have to de-commit. You can't fund them. To fund them-- it would be amazing. I mean, if we funded $123 trillion of future liabilities, that's six times GDP. If we did that over a 60-year period, we would have to take 10% of our GDP every year and put them aside into funding these liabilities. So we'd go from an economy which is 6% in deficit-- we'd have to go to one that's 10% in surplus. So it would be 16% swing from where we are today. So we cannot fund these liabilities.

So what has to happen is, we have to raise the age of entitlement eligibility. And we're going to have to cut people out, even though we told them that they were paying into the system as an insurance program for Social Security. And that will happen, and it'll happen remarkably easily.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Do you think the politicians will do that, though? Because they've made all these promises?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Because the awareness of the trajectory will become too obvious. And so people will say, you know what? I know I was supposed to get Social Security when I was 65, but you know what? I guess it's OK if I get it when I'm 72. And certainly the millennials are going to have eligibility that's probably 75. And some people, like me, won't get anything. So that's just what has to happen.

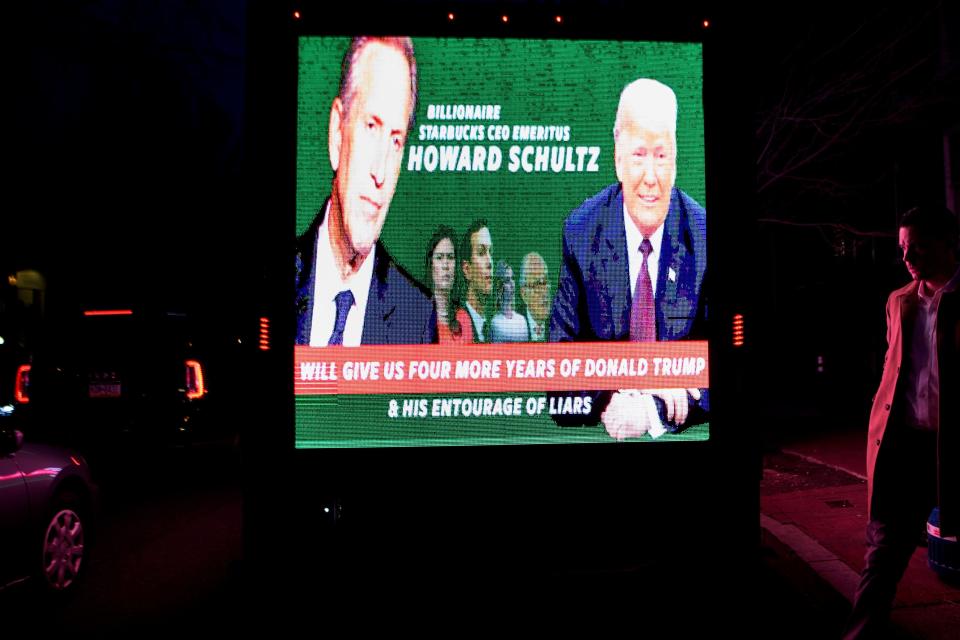

2020: Four candidates could get financial backing

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, I probably won't get anything either. Do you think that a third-party candidate, someone like Howard Schultz-- I don't know if others will enter, but he is specifically talking about the nation's dire financial picture. Do you think someone like that might actually stand a chance?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: No. You're not going to win in 2020 talking about debt, unless we have a recession first, and we're running a $3 trillion budget deficit, and then maybe you'd get that. It's possible. It's certainly plausible we have a recession before November of 2020.

But I don't really expect that a Howard Schultz out of nowhere, a private sector guy, would show up as a centrist candidate. I thought that there would be-- and I still think it's quite-- possible that Howard Schultz kind of just disappears. I'm not sure he's going to have the stomach for this. He did this nice, genteel book signing thing when right after he said he was thinking about running for office, and I think it was 23 seconds into the official interview with some fellow at CNBC, where he started getting heckled.

JULIA LA ROCHE: I was in the room.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: It just seems to me, I don't think he expected to be insulted, profanely insulted, by somebody 23 seconds into his coming-out party. So he's disappeared into his shell a little bit since. Then he's made some pronouncements that he doesn't like the Green New Deal concept.

But I really think it would be more like Trump, but maybe runs if there's no recession, and maybe a Mitt Romney decides he's got to come in as the old-line, more sensible Republican type of centrist. And then you'll get a socialist, for sure, running. I mean, there's plenty of them already. They don't all call themselves socialists. But somebody that's more old-line like Joe Biden might decide, well, I'm going to rescue the Democratic Party from this socialist cliff. So maybe you'll get a Biden and a Romney and a Trump and, as a placeholder, Bernie Sanders type of thing.

And I think all four of those would get funding. Clearly, there's funding for socialists. Clearly Trump-- he's already raised tons of money. He's way ahead of where Obama was for his second-term run. So they'll be funded. I'm sure Romney could get funding, and I'm sure Joe Biden could get funding. So I think you could have four candidates that have financial backing.

And I'm not sure that Joe Biden has any message whatsoever. I'm not sure Mitt Romney really has a message, other that he doesn't like Trump very much. So it's not clear at all those would get votes. But I think there's still enough of a residual of what used to be the Democratic Party-- like Bush is-- and what used to be the Democratic Party, which is Clinton. Of course, those two are exactly the same. It's not a coincidence that it was Bush, Clinton, Bush, then Obama, which is really Clinton. So it went out for a long time. And I think there's enough residual of those centers of influence that there could be some support there.

DoubleLine today and the investment opportunities it sees

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, let's move beyond politics, because I actually want you talk about you and DoubleLine. This is your 10th anniversary, I believe. 10 years running DoubleLine.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Thank you.

JULIA LA ROCHE: You've been in the business for over 35 years. You are the bond king now. That's what people say.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I never invited that, but that became prominent in the media.

JULIA LA ROCHE: You're a prominent bond investor. Most of DoubleLine's strategies are in fixed income. But I've noticed that you have been diversifying a lot lately. So I'm curious-- where are you finding opportunities, and what's exciting to you?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Well we've been diversifying, first of all, because we could. We were approached by Barclays Bank to run a smart beta equity fund using someone that they were working with, Dr. Shiller, the Nobel Prize winner, on the relative CAPE ratio. And it turned out that that strategy had tremendous success. I think it's the best-performing large-cap strategy in the country since we launched it. And that was good, because it was successful, and it's over $10 billion.

We started a liquid real estate fund, which I think is really interesting, with Colony Capital, which we've just started launching, that actually invests in all manner of REITs, that are brick and mortar REITs, but also includes digital assets. It's not just malls, like malls and nursing homes. That's part of it. It's much bigger than that.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Almost like newer economy.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Yeah. A lot of it's new economy, like satellite towers and stuff. And that uses a smart beta approach, too. It just got started. We'll see if it works. We launched it at a great time. I mean, it was like end part of last year, which is a great time to launch anything, because markets have exploded to the upside.

But right now, in the fixed-income market, the strange thing is, I think the most exciting thing is the two-year treasury. Not that it's great, but it yields about the same as the 10 year. It's a 2 and 1/2, which is OK. I just think that interest rates have a bias to rise on the long end.

And I think it's late enough in the cycle with enough leverage in the corporate economy that if we continue to roll on with attractive gains and risk assets, I'm pretty sure it's at the end of the game. And you're going to be better off waiting and foregoing those gains, because your opportunity set will be vastly better when the next recession comes.

And as we said earlier, can't really see a recession, say by middle of this year-- well, we could always get surprised, but our indicators don't show it. But they are starting to show signs of cracking. Not convincingly that you have to act today, but when the next recession comes, there's going to be an outrageous opportunity in corporate credit, and I think you want to own none right now. None. And instead, you just say, I might lose a few percent versus playing in that game. But when it goes down-- well, we saw what happened from October 3 until Christmas Eve. I mean, there was a pretty big drop. And I think that that's just kind of a taste of things to come.

What Gundlach said in June of 2007

JULIA LA ROCHE: It reminds me when you called the housing meltdown, and you were one of the first to put capital to work. Is that what you're seeing when it comes to corporate?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Yeah, I called it, but I wasn't one of the first to put capital to work I actually raised a distress fund starting in February of 2007 and it was an interesting period, because the institutions that I was suggesting this idea to-- they were debating whether I was right more than anything. They were saying, well, no one else says this. You say the housing price is going to drop 35%, which I said in Barron's in December of 2006, when they were down by 1/2 of 1% so far. It's a long story I won't get into it for time.

But I knew what was going to happen in the housing market. It took a little longer than I thought, maybe by about six or eight months. But then what I became known for, as I spoke at a very prominent conference in June of 2007, and I went on stage, not fully sure of what I was going to say. I didn't make notes or anything. I had some slides. And all of a sudden, it seemed like it was the right moment, and I made the declaration-- I'm going to get to the credit markets later on in this talk. But I'll just give you a hint. Subprime is a total unmitigated disaster, and it's going to get worse.

That phrase was captured in the media on five continents. And at that time, the subprime sector, the AAAs, the AAs-- they we're still trading at 100 cents on the dollar. They hadn't dropped at all. Zero. And they really started dropping in earnest in the first part of 2008, later part of 2007.

I didn't really start putting money to work until March of '08 after the Bear Stearns collapse, because by then, the prices were low enough where you were pretty sure to get more than your money, what you invested, your cost. You were likely to get that back. But I knew it was going to go lower. I announced to my investors in March.

At that moment, March of '08, I said, I just want you to know, I value transparency. I'm going to start buying credit. I warned this is going to happen. I said the prices are going to collapse. I think they're low enough, then, to start buying them. But I want to buy so much of this stuff that it's probably going to take us a year. And we didn't really get fully invested until March of '09, which as good luck would have it, turned out to be the bottom.

So yeah, I think something along those lines is going to happen, but it's not going to be in the securitized markets. It's going to be in the market that's mis-rated today. When you're looking for distressed opportunities in fixed income, the best ones come from things that are mis-rate going into the problem, because the people that buy investment-grade corporate bonds are looking for safety. They think they have safety. When you buy a AAA-rated subprime floater, you're a AAA person. You didn't sign up for a lot of risk. You signed up for a little bit of reward, hoping that the risk was de minimis.

But then it ends up being a big risk. And so it's not surprising that the people that sign up for safety sell when the market goes down, because their eyes have been opened, and they now realize that they were fooled. They thought it was safe, but they were wrong. And so they were lied to. And so they decide, I never signed up for this. I'm getting out before it gets worse. And that creates another layer of selling.

So for example, there was a lot of buying of stocks in the latter part of December. And by all appearances, it seems to have carried into--

JULIA LA ROCHE: Right. They might be feeling good.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: --2019. I think the people that bought at the best levels of late December-- I think that they will sell at a lower level than what they bought in it, for that same type of a thing. They bought in. They thought it was a buy at the dip. They feel emboldened by it. They've gotten an economic and psychic reward so far. But once that buy goes underwater, it will accelerate the selling, because those people will turn into sellers, I think. And that'll happen in the corporate bond market, too.

Bear market: Last year’s selloff just a ‘taste of things to come’

JULIA LA ROCHE: Do you think there's another down coming? Do you think this is a bear market that we're in?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Yeah. It's a bear market. I mean, a bear market has nothing to do with this 20% arbitrary thing. It has to do with something crazy happening first, and then the crazy thing gives it up. And yet more traditional things continue to march on, but one by one, they give it up.

So what was the crazy thing? Bitcoin. Bitcoin was the crazy thing. Bitcoin going from zero to $20,000 in a straight line-- it was crazy. And you knew it was crazy because other things started to happen that were truly insane. There was this thing called CryptoKitties. It wasn't a cryptocurrency. It was a collectible, but it had the name "Crypto" in it. And they were each unique, but there were cartoon drawings of cats. And there was actually a moment where one sold for over $100,000. Of course, they're worth $0 today.

But that is a sign. That's like Pets.com back in the late '90s. That's like pick-a-pay, negative amortization, 120 LTV loans in 2006. Bitcoin was insane, and it crashed starting in December of 2018. Then the global stock market peaked a month later. Then the transports peaked, the utilities peaked. Then the Dow Jones industrials peaked. Then the S&P peaked. Then finally, the NASDAQ peaked. And then it was down to five stocks. And then it was down to four stocks. Then it was down to two, Amazon and Apple. And then, on October 3, it was over.

And so that's how a bear market develops. And I think that it's been saved by the Fed's pivot, and it's been saved by the bond rally taking some pressure off the stock market. But if the long end of rates starts to rise, as I expect, and if we break through 350 on the 30-year, I think it's over, because the competition from the bond market, particularly against a climate of limiting one of the engines of stock price appreciation, which is buybacks, is thought to be potentially in jeopardy.

I mean, it is interesting that a Republican is proposing legislation to curb buybacks. That shows you that Marco Rubio wants to get in front of this issue before somebody on the other party claims it as their own. So the support for limiting buybacks seems pretty high.

Cannabis seems like ‘mania’; smoking stats are ‘horrifying’

JULIA LA ROCHE: So you mentioned bitcoin, which was the mania. Do you think there's another mania-- I'm thinking, maybe cannabis? That's the one that people are talking about now. If you have an opinion.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Yeah. I've got young guys working for me that are big believers in the cannabis thing, and they claim that it's all about getting shelf space and branding and getting bought out by another big company. That's the game. I mean, it sounds plausible to me, but I don't know. I'm pretty simplistic. I don't know why there isn't a corn mania. How come there isn't a corn mania?

JULIA LA ROCHE: Yeah, why not?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Grow corn, too. I don't understand why, just because it used to be illegal, that somehow it's got this special magic to it. But it's interesting. The cannabis thing does seem kind of like a mania. I mean, people probably make a lot of money in some parts of it. But that's just not for me. I've no interest in mania stuff. I just watch amusedly from the sidelines.

What I do find that's a little bit scary is, I saw a statistic this week that the increase in smoking among high school students, year over year, 38%--

JULIA LA ROCHE: Because of the Juul? Vaping.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: It's because of vaping.

There is an explosion in smoking, which I suppose is probably a gateway for the cannabis industry. So maybe there's something there. But I find that to be an incredibly horrifying statistic. In one year, 38% increase, and now over 50% of high school kids are either smoking-- they're probably mostly vaping, I think, which is probably far worse, far worse than traditional cigarettes. I don't know. I've never been a cigarette smoker, but I wouldn't go anywhere near any of this chemical concentration stuff.

Dealing with the noise and avoiding groupthink

JULIA LA ROCHE: One thing that's always been interesting to me, Jeffrey, is, you're out here on the West Coast, and people do look to you for your various calls and views. And I'm just wondering, how do you sift through the noise? How do you get your information? What do you look at?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I look at news wires more than anything else. And I try very hard to pay no attention to what other people think. Sometimes people do things. They say, name somebody that you admire or something. And I was thinking about it, and a person I really admire is someone that most people don't know the person's name. His name is Donald Judd.

And Donald Judd was one of the great-- call him a sculptor if you want to-- of the 20th century. He broke rules and made people angry, because he actually didn't make the sculptures himself. He designed them and then sent them off to machine shops. And this was back in the '60s when he started. And that was considered to be-- that can't be art, because it doesn't have the artist's hand in it.

But Donald Judd was an art critic in New York City, and then he tried his hand at painting. And he as an art critic, he was very involved with the art scene, which was very vibrant in the late '50s and early '60s. New York was the artistic capital of the world, having moved there from Paris. And Donald Judd became very involved as a critic and then a painter.

And then he decided that being in the New York art scene was detrimental to his own artistic vision, because he was too influenced by Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol and Eva Hesse and all these other luminaries of the time, and that it made him distracted, that other people's ideas were confusing him and taking his vision of his own art and making it more diluted.

So he did something very radical. He got up, and thanks to the generosity of the Dia Foundation, who bought an old Korean army base that he had served at in Marfa, Texas-- which is the definition of the middle of nowhere-- he set up his art studio there in the old barracks and the old artillery sheds. And he wanted to get away from all of the noise. And by far, his best work is in Marfa, Texas. It's the greatest art installation I've ever seen. It's hard to get to. It's 300 miles away from any commercial airport. So you have to fly in and drive, or you've got to fly out to jet strip there.

And that really spoke a lot to me, because I realized that doing things like-- there's some events that I get invited to all the time, groupthink events. They call them Titans' Dinners and stuff like this. And all these hotshots are there, all these names of people that we all know in this business. And they'll be there, and you can sit there, and people share ideas.

And I did a couple of those years ago, and I would sit there, and here's Mr. Great number one, and he's massively bullish on Apple. And then they turn to Mr. Great number two, and he's massively bearish on Apple. And both of their arguments sound really good to me. So I've suddenly like, I don't know what I think now about Apple. I might have walked in the room thinking something positive or negative, but now I'm just confused.

Correlations: I have a whole team looking for them

And so I think what's important is to look at the news flow and watch for those times when the news doesn't change, but the interpretation does, or the news does change, and the interpretation doesn't. Those are moments where there's this gap of opportunity. And I think my primary skill has always been living in that gap in a way that's quicker-- maybe it's just because of the way I operate, I don't know-- than other people. And so that's the real key, is to look for harbingers and instances of the cusp of change. When you actually get a moment, you can act on it.

Strange things happen. I remember that Ben Bernanke, when things were looking pretty grim back there in 2011 or so-- he said, we're going to keep short-term interest rates at zero for at least three years. He pre-announced three years of zero interest rates. And shockingly, many instruments in the bond market that were sure to profit tremendously from zero interest rates for three more years-- they didn't go up in price for half a day. And I bought them all.

And I was like, why aren't people buying them? I said, I don't know, but they should be like 20 points higher. And they were 20 points higher about two weeks later. But they were actually there to be had. Because people want to see the idea that they have get ratified or corroborated by a crawler on some financial program. And then, oh, I see, now it's safe to do this, because everybody else is saying that this is the conclusion you're supposed to draw. But by then, it's priced in. So by the time it's safe and you have a confirmation that your idea might be broadly embraced-- by then, it's too late. So that's really the key.

Also, just trying to find relationships. I have a whole team, that what we do is, we just look for correlations. That might be common sense, but then you verify them, some things that just correlate well. For example, things like the Fed's underlying inflation gauge, which doesn't get nearly enough attention. It correlates incredibly well to CPI, core CPI, on about an 18-month lead basis. It's got about an 80% correlation. Nobody knows about this. Well, we do. Unfortunately, I speak to people like you, and I give my ideas away.

But it's OK, because relationships don't hold up forever. The world changes. The variables change. The coefficients change that drive things. And so it's really important that you just stay on top. That's why I do what I do. I mean I could have retired a long time ago. I find it very interesting as a way of processing human behavior, society, and just understanding what makes the world go round.

Recruiting: ‘I generally like to hire people who either I know or who know nothing.’

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, I want to follow up on a couple of things here. You mentioned that your team here-- and I've met a few folks from DoubleLine in the past couple of years. How do you think about talent? What do you look for when you're hiring someone?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I generally like to hire people who either I know or who know nothing. I don't like bringing in people from other firms who have eight years' experience because they've learned some other way. And not that the other way is wrong, but it's not the way we do things. And it's not that we do everything perfectly-- there's only our way. But I like people who are right out of school, because that way, they don't have to be untrained from what they thought they learned somewhere else.

And then I like people that I know the way they think. So we like people that are very analytic.

We like people who believe in shared success. I tell people when they start working here, at many firms, you succeed by killing the person next to you. If you even go in that direction, you're gone. I want people to want the person next to them to do well, because the person next you're doing well means the firm does well. And so we have a shared success philosophy. And it comes from the top because, I never yell at anybody. My philosophy is, everything that goes right, the team did it, and everything that goes wrong, it's my fault. And I think that people appreciate that.

‘Tax policy is pretty strange’

JULIA LA ROCHE: You mentioned that you could have retired. I'm sure people ask you, well, you're successful, you can retire anytime. What is it that keeps you going? What is it that drives you?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: It's not really working, is the thing. I just process the world through human interaction, which in this particular instance reveals itself through financial markets' movements. And so I just sort of like it. Also, I'm committed to a couple of terrible enterprises that basically need a lot of money. So that's a good reason to work, so that it can be funneled not just to the Internal Revenue Service in the United States Treasury-- which I am a very significant contributor to-- but also something I think matters, rather than just some rathole of administrative waste.

And so I don't really resent the fact that I pay so many taxes. It's sort of a privilege in a certain sense. But I also want to be able to see results for the money that I'm giving away--

JULIA LA ROCHE: And have impact.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: And it's a very big impact when it doesn't go through a bureaucratic machine.

JULIA LA ROCHE: How about when folks are saying, they should have a 70% marginal tax rate on the wealthiest--

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Well, my marginal tax rate is presently combined, California and US, 52.6%. I am deeply offended when people tell me, no, it's not. I actually have heard people say that to me. No, it's not. Rich people like you only pay 15%. I'm telling you, it's 52.6%. All right? So that's because California's 13.3%, and then there's federal, and there's other things.

So if they raise it to 70%, that would be a 33% increase. I would go to 85.6%. I really think I would stop working.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Yeah. Who would even work at that point?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I really think I would stop working at 85.6%. So the tax policy is pretty strange, because a lot of people that are in my financial position really do pay low taxes. I remember Mitt Romney-- I think he had a 14% tax rate on some tax return that he revealed as part of his run for president. I mean, 14%. That's just amazingly low. I agree, that's ridiculous. But instead of raising me from 52.6% to 85.6%, I think the 14%-ers should come up to 52.6%. That's what should be happening. But I guess I'm just in a very, very small minority, and so the others protect the 14% potential. So tax policy is really weird. It's really weird to me that people making exactly the same amount of money pay very, very different tax rates.

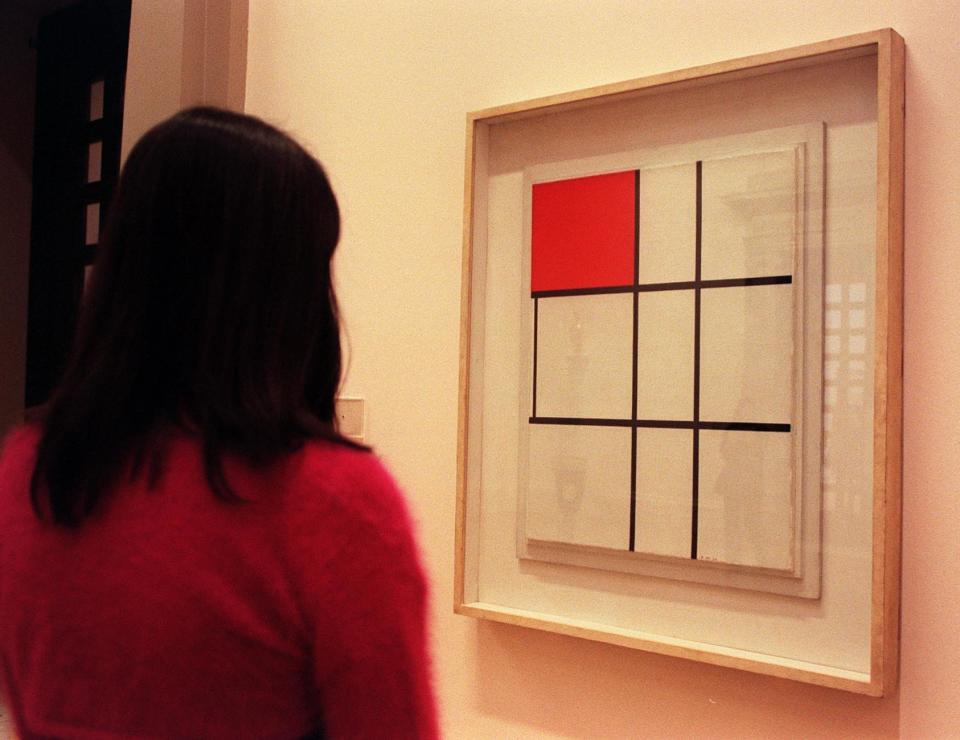

Art and how DoubleLine got its name

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, I know one of the areas that you're really focused on when it comes to philanthropy is art, and that you are a passionate art collector. How do you think art influences your career, your investment career?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I don't really think it does. I think it's just very different. I mean art is very subjective. So I think it's a balance, more than a tie-in to what I do. What I do, running money, other people's money, is amazingly, at the end of the day, not objective as to whether you've done a good job or not. It's actually painfully objective, because it's a number to two decimal points or more. That's your number versus that market number versus some other investor's number. And there's no getting away from that. It's incredibly easy to judge. Whereas art is incredibly subjective, and you can't put any kind of definitive number on it. And so I think it's a yin and yang thing.

JULIA LA ROCHE: One thing I do like is when you get off the elevator, you see DoubleLine. You see that the painting that you actually did. Tell us the story. What does the name DoubleLine mean?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Well, it's interesting. I for some unknown reason, in about 2005, woke up in the middle of the night-- which I almost never do. I'm not one of these can't sleep at night people. I often get asked, what keeps you up at night, and I say nothing. I mean, there's nothing. It keeps you up at night.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Sleep well.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Yeah. So I woke up in the middle of the night, and for some reason, I was obsessed with this idea, which I never thought about before. If I started my imagined firm, what would I call it? And it was just kind of a fun thought experiment. And so many names are meaningless. They're named after an intersection in a city or a Greek god or some sort of gibberish like First Financial. If there is one, I'm not trying to insult them, but names don't really mean anything. Or rivers or something like this. Lakes. Geographic places.

I was like, I'd want a name that meant something. And so what would be a good name? And I had just bought my first Mondrian. And it's his last great classical painting, where two devices are used. One was an early device called a progression, which is basically rectangles that progressed. Another was a device he came up with in 1931, which is called the double line. And the double line is a further ambiguity between line and plane, because there are two lines that are close enough together that they look like two lines, but they could also be interpreted as defining the negative space of a rectangle by bordering them.

So I had this picture and just got the double lines. And I was thinking, a double line. That would be a really good logo. And then I realized that it had a meaning, that the meaning was, in everyone's life that they experience, more frequently. People go, double line? I don't-- what? There's a double line in the middle of a highway. And by law, you're not supposed to cross it but it's really there for your protection. At least, you like to think it's there for a reason. And the reason, of course, is it's not safe.

And so I realized, hey, that's pretty neat, because I'm really risk-averse. I think more about what you shouldn't do than what you should do. And what you shouldn't do is take fatal risks. That's what kills, particularly, fixed-income investors. If you buy a lot of junky bonds, and they default, your money is gone forever. If you buy a bunch of mortgages and they refinance at the wrong time, you lost money forever. So it's what you don't do. And I thought, that's perfect, because it defines things that we won't take, certain fatal risks.

I was giving a speech years ago now. It was way back in our second year of business or something I was giving two speeches in one day. One was in Bakersfield, and one was in San Luis Obispo. And Bakersfield is really interesting. It's a very wealthy community. You wouldn't think so, but it is. There's a lot of farmers, and there's a lot of oil there. And I went to give the speech, and a lot of guys showed up in overalls. They were farmers. There was a guy who was like the number-two potash guy in the world or something. These billionaires, and they're showing up in overalls.

And then I said, hey, I'm looking at my map. I've got to go to San Luis Obispo. There's two roads, and I can't really tell which is the more efficient route. And the guy says, whatever you do, don't take this one. I go, well, why not? He said, it's called Blood Alley. I said, really? He goes, yep. There's more fatal head-ons on that road than any other one in the state. And the reason is that it's tractor country, and it's very winding, and it's one lane each way, and tractors go slow, and people are impatient. And they just decide they're going to go for it, and a truck's coming the other way, and they get wiped out. And that's why it's called Blood Alley.

And I said, that's fantastic. That's exactly-- and I started talking about the name of the firm and everything. It was pretty interesting. So we took the other road, obviously. It was pretty cool. We went over the San Andreas Fault, where the road has a massive whoop-ti-doo in it. It was really surprising. And someone went was like, what was that? And someone said, that was the San Andreas Fault. That's right halfway between those two. So anyway, the double line really came to life with that guy in the overalls.

Facebook’s ‘big problem is obviously their business model’

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, before I let you go, we've seen you on Twitter, and the last thing I want to know-- when did you join?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: It was at Ira Sohn in 2017.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Ira Sohn, that's right. That's right. So what's your take on social media now that you have somewhat of a presence?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: I have no presence. I follow nobody.

JULIA LA ROCHE: But you tweet a lot, and you get a lot of retweets.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Well, I don't tweet that much. But I do sometimes. I'm just trying to give people an insight into what I'm really thinking. There's a lot of misreporting that goes on in financial media. There's a lot of people that report on-- but somebody reported on, something reported on, like that old telephone game that you do in first grade, where you go through the class, and it ends up starting to be, the sun is shining, and the last person says, the cow was in the hotel, and you can't figure out how the message got so altered. But that happens with re-reporting.

And I like to tell people what I really think. So I like interviews that are live, or ones that I do a written statement, because I find-- when I do webcasts, for example, the stuff that gets reported-- more than half of it's wrong. I mean, I didn't say that. They'll leave out the word "not" and then invert the meaning. So I like to have the Twitter account where, if something like that goes off, I can say, this is truly where I'm coming from.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Then we'll never see Jeffrey Gundlach on Facebook?

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Never. Never. Never on Facebook. I don't know what Instagram is. I've never downloaded an app in my life.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Do you still have an opinion on Facebook? I do remember you spoke about it. It was a pair trade, so maybe last year.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: And it fell a lot. It's rebounded back up. I just think that Facebook-- their big problem is obviously their business model. And I talked about things that are safe ended up being unsafe. I think that's Facebook I mean, they sold themselves as comfortable and safe, but they're really just a diabolical data collection monster. And they're unrepentant.

And I just saw yesterday they were talking about more regulation in Europe in the UK. And when the regulators show up, usually, the stock prices go down. Health care had a meteoric rise until the regulators showed up a few years ago, and then a big decline. So I don't really trust Facebook. So the fact that I don't trust them makes me not like them, and the fact they don't like them makes me want their stock to go down.

JULIA LA ROCHE: Well, Jeffrey Gundlach, CEO of DoubleLine Capital, it's been a pleasure. Thank you so much for your time.

JEFFREY GUNDLACH: Thanks again for coming.

—

Julia La Roche is a finance reporter at Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter.

Gundlach: The U.S. economy seems to be on a ‘suicide mission’

Gundlach: Debt-financed stock buybacks have turned the market into a ‘CDO residual’

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.