JOBS WEEK — What you need to know for the week ahead

After an extremely busy week which saw markets take big swings both up and down, the final jobs report released in 2017 will greet investors as the biggest economic story in the week ahead.

The November jobs report is due out Friday and is expected to show the second-to-last month of the year enjoyed strong payroll growth with economists forecasting nonfarm payrolls grew by 200,000 in November. The unemployment rate is also forecast to hold steady at 4.1%, a 17-year low.

Elsewhere on the economic schedule, investors will get readings on the services sector and consumer sentiment. On the earnings side, things will be a bit slower with results expected from AutoZone (AZO), H&R Block (HRB), Dollar General (DG), and Broadcom (BRCM).

In Washington, D.C., investors will monitor progress on tax reform after the Senate in the overnight hours on Saturday passed its version of a tax bill. The Senate and the House will now work to reconcile their bills to present a unified plan to President Donald Trump to be signed into law.

Markets will also keep an eye on any new developments in the Mueller probe into Russian interference in the U.S. election after President Donald Trump’s former national security advisor Michael Flynn plead guilty on Friday to lying to the FBI about his contact with Russian officials.

This news initially roiled markets, sending the Dow down by as many as 400 points on Friday, though the major averages recovered through the day and closed the week mixed as the tech-heavy Nasdaq lost ground while the Dow and S&P 500 both logged gains.

Economic calendar

Monday: Factory Orders, October (-0.4% expected; +1.4% previously); Durable goods orders, October (-1% expected; -1.2% previously)

Tuesday: Trade balance, October (-$47.4 billion expected; -$43.5 previously); Markit U.S. services PMI, November (55.3 expected; 54.7 previously); ISM non-manufacturing PMI, November (59 expected; 60.1 previously)

Wednesday: ADP private payrolls, November (+190,000 expected; +235,000 previously); Nonfarm productivity, third quarter (+3.3% expected; 3% previously)

Thursday: Initial jobless claims (240,000 expected; 238,000 previously); Consumer credit balances, October (+16.35 billion expected; +$20.83 billion previously)

Friday: Nonfarm payrolls, November (+200,000 expected; +261,000 previously); Unemployment rate (4.1% expected; 4.1% previously); Average hourly earnings, month-on-month (+0.3% expected; +0% previously); Average hourly earnings, year-on-year (+2.7% expected; +2.4% previously); Wholesale inventories, October (+0.2% expected; -0.4% previously); University of Michigan consumer sentiment, December (99 expected; 98.5 previously)

Do corporate tax cuts work?

Early Saturday, Senate Republicans passed their version of a bill to cut taxes which paves the way for President Donald Trump to sign one of his primary campaign promises into law in the coming weeks.

Senate and House Republicans will now come together to reconcile the differences between their bills to find a unified path for lower corporate taxes to bring to Trump’s desk.

And while supporters of the bill may list a litany of reasons for why this move was needed, or why this move will be good for the economy, the Trump administration has long maintained that economic growth would be the main result of cutting taxes. And this economic growth the thinking went, would be the direct result of corporations increasing investment due to lower tax burdens.

Kevin Hassett, the chair of Trump’s council of economic advisors, has said that American families would see $4,000 in additional wages over the next decade as a result of increased investment from corporations benefitting from lower taxes.

But Joe LaVorgna, chief economist for the Americas at Nataxis, outlined in a note circulated Friday that the last several decades of evidence lends little to the idea that lower taxes boost investment in a meaningful way.

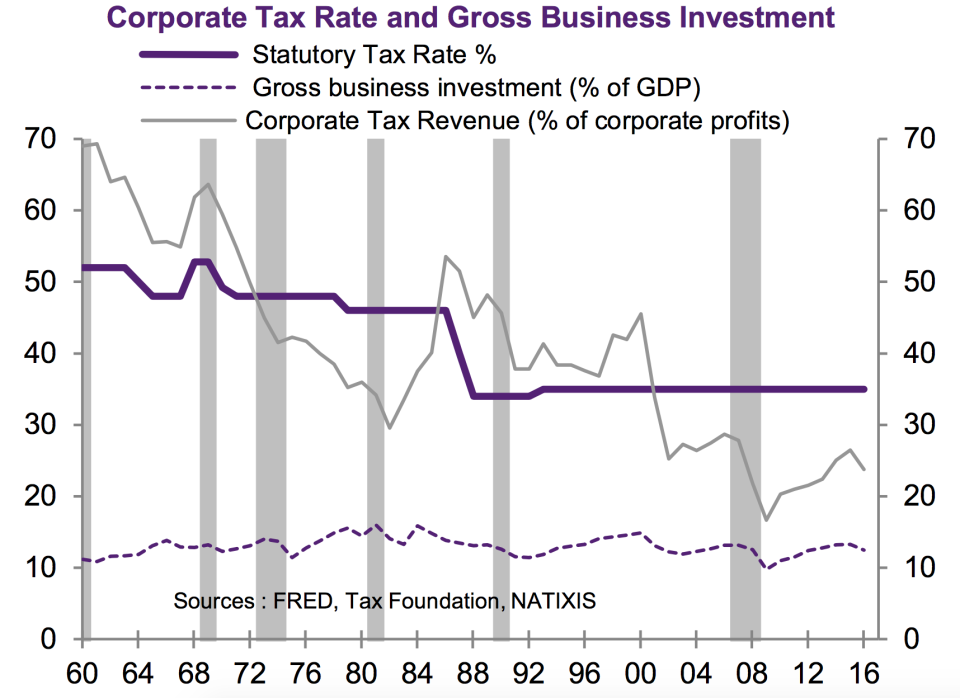

LaVorgna writes that gross business investment as a share of GDP since 1960, averaging 13% over time with a standard deviation of 1.3%, meaning that there have been few major changes in the investment tendencies of American businesses.

In 1986, when the Reagan administration passed its tax cut — which Trump has so often said he would seek to outdo — the corporate rate fell from 40% to 34%. This lower rate, however, did not shift the investment habits of corporations. In fact, investment has fallen in the roughly thirty years since this cut passed relative to the 26 years tracked by LaVorgna before this cut, though corporate taxes have been lower during that period.

“From 1960 to 1986, the corporate tax rate averaged 48%, and the gross investment share of GDP averaged 13.3%,” LaVorgna writes. “From 1987 to present, the corporate tax rate has averaged about 35%, and the gross investment share of GDP averaged 12.7%. Even if we take out 2009, when the share plunged to a record low of 9.8%, the average increases just a tenth to 12.8%.

“Clearly there is no correlation between the tax rate and the share of business investment in the economy.”

Skepticism towards the positive impacts that lower corporate tax rates would have across markets and the economy, however, is nothing new. Back in February we were writing about work that showed corporate profitability — seen by many as the obvious beneficiary of a lower tax burden — has had little correlation with the overall corporate tax rate.

Now, corporate commentary during third quarter earnings season indicated there was some optimism around tax cuts passing, but few specifics were given on what companies would do if they were to see a lower U.S. corporate tax rate in the coming years. Goldman Sachs CFO Marty Chavez said on the bank’s earnings call that companies looking to make deals weren’t working around the uncertain prospects for a new tax code.

But perhaps the clearest explanation of what the tax code can and cannot do for the economy came from NYU finance professor Aswath Damodaran, who told Yahoo Finance in January 2017 that the, “The tax code is a bludgeon. When you change the tax code trying to make companies do the right thing, you almost always have a law of unintended consequences.”

Damodaran added that, “tax codes have never been effective behavior modifiers.” The promise of investment against the reality of investment in a lower-tax environment has so far borne that out.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: