'No rhyme or reason': 'Non-essential' businesses say coronavirus closures violate the Constitution

American businesses deemed non-essential and struggling to survive during the COVID-19 outbreak are filing lawsuits to challenge the constitutionality of government-forced closures. The U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on one such challenge on Wednesday, when it refused to lift Pennsylvania’s shutdown order.

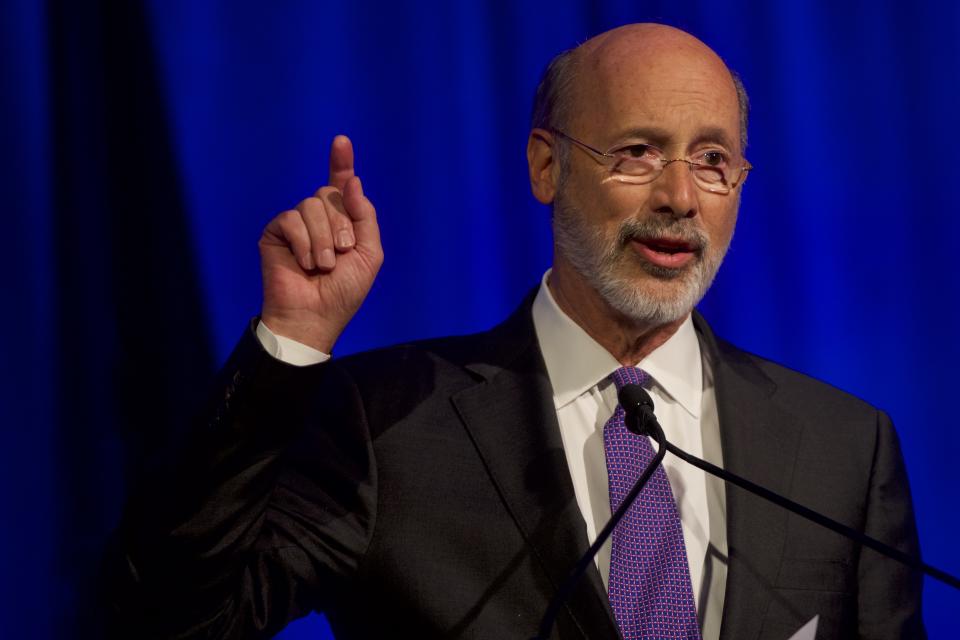

On Monday, the high court received a response from Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf ordered by Justice Samuel Alito to address a request from three petitioners to halt the state’s March 19 emergency order while the court considered whether to review the case.

The request came after the state’s supreme court issued a 4-3 ruling upholding the governor’s order, which adopts an exemption system for “life-sustaining” businesses to remain open during the pandemic. The petitioners argue the order violates both the U.S. Constitution and state law. Separate cases challenging the constitutionality of mandated businesses closures have also been filed in Michigan and Minnesota.

Pennsylvania’s order prohibits any person or entity from operating a business that is “non-life-sustaining” regardless of whether the business is open to members of the public. Violations, the state’s guidance warns, are punishable by imprisonment and fines.

Its list designating business as life-sustaining versus non-life-sustaining has been amended multiple times, and resembles decisions made by other states to keep intact industry supply chains such as health care, food and energy, manufacturing operations for certain minerals, chemicals, plastics and cleaning supplies, and semiconductors, and maintain public utility services.

Some of the state’s non-life-sustaining business designations include residential construction, most retail operations, certain civil engineering projects, textile manufacturing, and computer and electronic product manufacturing.

“There's no rhyme or reason as to what our governor is considering life-sustaining non-life-sustaining,” Jim Roth, general manager for Blueberry Hill Public Golf Club, one of the petitioners to the Supreme Court, told Yahoo Finance. “Obviously we were considered non-life-sustaining, although a beer distributor is considered life-sustaining and they never had to close a day, yet I close down completely for six weeks.”

COVID risk allows government leeway

While legal experts acknowledge that the extraordinary, unprecedented risk presented by COVID-19 allows governments a good deal of leeway to enforce orders restricting business activities, the current cases show there is room to test their reach.

According to Gibson Dunn & Crutcher attorney Avi Weitzman, businesses that challenge the constitutionality of such orders could raise at least four potential theories to try and make their case.

“When the line drawn between essential and non-essential businesses becomes arbitrary and irrational,” Weitzman said, “I think courts will start second guessing...the lines the executive has drawn.”

The most promising of the constitutional challenges, Weitzman suspects, will be those based on arguments that mandatory closures for businesses deemed non-essential violate the 5th Amendment’s “takings” clause, a provision that prohibits governments from taking property without adequate compensation.

The claim is at the heart of a separate Pennsylvania case, a proposed class action lawsuit filed by a musical instrument manufacturer against Wolf and the state’s health department over required shuttering of “non-life-sustaining” businesses.

“It’s called a regulatory taking — that the active regulation is so onerous that it has taken away property without sufficient reason,” Weitzman explained.

In their complaint, the plaintiffs argue that despite having a legitimate public purpose “COVID-19 closure orders make it commercially impracticable” for non-life-sustaining businesses to use their property for any economically beneficial purpose. In essence, they argue, the orders effectively appropriate or destroy the business property as a whole.

Because some businesses can operate while also observing social distancing and other safety measures, Weitzman said they may have legitimate takings clause claims if they can show their operation does not pose a substantial enough risk of spreading COVID-19 to justify a shutdown.

Georgetown law professor David A. Super disagrees. “Restrictive regulations, even that destroy most of the value of a business or property, are not generally takings,” Super said.

The rule, he said, was established by the U.S. Supreme Court roughly 100 years ago when it held that zoning regulations applied by cities, counties, and states remain legal, as long as the regulations do not involve government seizure or taking control of the property.

While Super acknowledged that coronavirus restrictions are indeed ravaging value of some businesses, he said declines alone are not enough to prevail in court because governments are given leeway to draw crude lines, such as the ones delineating essential versus non-essential businesses. To prevail, he said, a business would have to show there is virtually no connection between the government restriction and its purported goal.

“If you see something that is completely absurd….then you can imagine the court saying, ‘Well you're using the emergency as pretext for something different,’” Super said. “But in general, in these emergency situations, the courts have understood that some uncertainty is inevitable, and that some line drawing is inevitable.”

Two other avenues of attack that businesses could use to challenge the constitutionality of coronavirus orders, according to Weitzman, include due process and equal protection claims.

A “serious denial” of constitutional rights?

Due process considerations are central to the Pennsylvania case now before the U.S. Supreme Court. The petitioners — a public golf course, state legislative candidate Danny DeVito, a timber company, a laundromat, and a licensed realtor — argue that the exemption system effectively singles out businesses, without judicial review. The lack of review, according to their petition, “constitutes a serious denial of the constitutional rights of petitioners and tens of thousands of Pennsylvania businesses that are similarly situated.”

Since implementation of the order, the golf club and timber company have been permitted to conduct business on a limited basis.

“I had zero income, although I still had to maintain my golf course. I still had to pay a crew. My expenses have been pretty much normal,” Roth, the golf club manager, told Yahoo Finance.

Roth said his course lost approximately $66,000 in April and about $20,000 in March.

“In golf, once you lose a day you just lose it,” Roth said. The club is now operating at reduced capacity, allowing only one person or couple per cart, a maximum of three people at a time permitted in the clubhouse, and with greens holes covered so that putts cannot be dropped in.

“The police were here three out of four days last week,” Roth added, explaining that the visits were from both State troopers and agents for the liquor control board. “I think I have a target on my back, because I’m the guy suing the governor here in Pennsylvania.”

Roth said he considers the pandemic “very serious” yet believes the golf course can be operated safely in his rural community where no county residents have been diagnosed with COVID-19.

In its response filed Monday, Wolf’s administration downplayed the plaintiffs’ challenge as no more than a public policy disagreement with the governor's determination as to which physical locations would remain open and which would be temporarily closed.

“Under Pennsylvania law, the Governor is responsible for employing the most efficient and practical means for the prevention and suppression of any disease. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this required delicate balancing: Close too few businesses, and COVID-19 would continue to spread uninterrupted, collapsing our health care system,” the reply brief states.

The brief added: “Close too many businesses, and people would be unable to access life-sustaining supplies. Striking that balance is not only consistent with constitutional principles, it is necessary to their protection.”

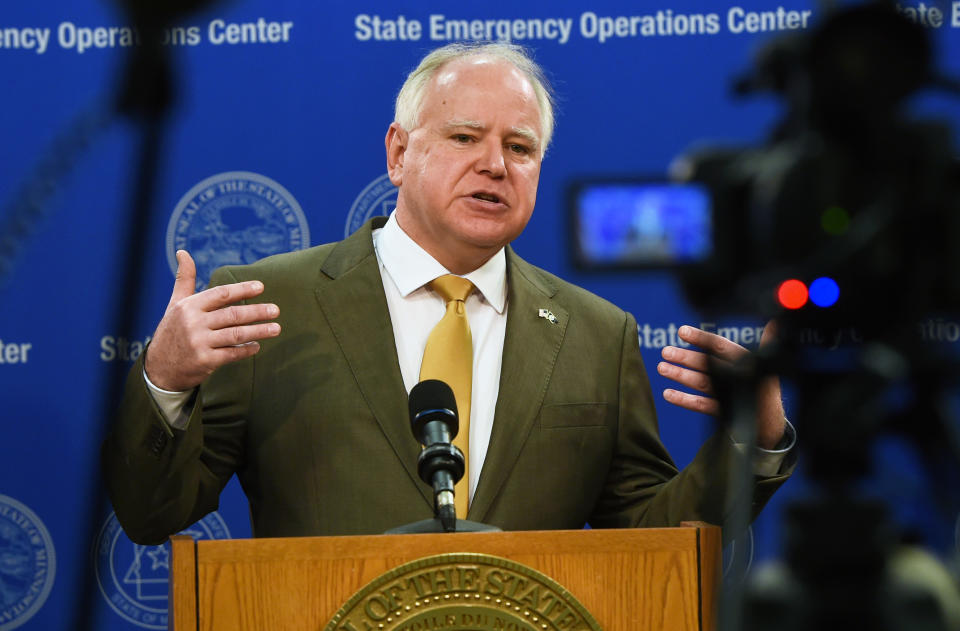

In a separate case, a group of 15 small business owners in Minnesota are also testing an equal protection claim against the state, alleging that Gov. Tim Walz’s categorization scheme designating which companies may remain open is unconstitutional.

To consider the constitutionality of a government’s financial, economic, or commercial regulation, such as the emergency orders enacted in response to the new coronavirus, courts are required to apply a “rational review” standard. For the order to sustain a challenge, a government is required to show that its regulation is rationally related to its interest in protecting public health.

The low standard makes it difficult for challengers to invalidate such orders, according to Super. As long as the order applies to an entire population, he said, the Supreme Court has historically permitted orders to remain intact, without requiring individual hearings.

Still, a fourth type of foreseeable challenge could arise based on the contract clause, where companies allege that closure orders impair a company’s ability to fulfill existing contracts, and in turn, leaves it in breach of its agreements.

Other constitutional challenges have been raised alleging state emergency orders infringe on freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

The Congressional Research Service summarized some of the constitutional challenges to government actions taken in response to COVID-19, noting that some pose scenarios not yet settled by the high court. In an April 16 publication, the organization wrote as to freedom of assembly that “while the Supreme Court has at times ruled that First Amendment freedoms must yield to certain exigencies, it has never squarely decided whether the government can completely ban people from gathering during a state of emergency.”

The agreement of four Supreme Court justices was needed to grant certiorari to the Pennsylvania petitioners, which would have allowed the Court to hear their case.

“We really think Mr. Wolf overstepped his bounds as far as what he can close,” Roth said. “He pretty well destroyed the whole economy for the state of Pennsylvania, and this is going to last a long time. And even though we are open...he can shut us back down, and that is why this suit is continuing right now. Quite honestly, if he shut us down again I’m not certain we could recover.”

Yahoo Finance requested comment from the Pennsylvania attorney general’s office, which is representing Gov. Wolf, and did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Editor’s note: This story was updated after the Supreme Court refused to lift Pennsylvania’s shutdown order, and to correct a reference to the commerce clause which should have referenced the contracts clause.

Follow Alexis Keenan on Twitter @alexiskweed.

Read more:

When Americans come back to work, we could see a ‘spike in litigation’ over coronavirus

‘The flood is coming’: Coronavirus could spur unprecedented wave of business bankruptcies

‘A very scary idea:’ How Google and Apple’s COVID-19 tracing could turn sick people into pariahs

Coronavirus: How the law can protect you if you can’t pay your rent or your mortgage

Follow Alexis Keenan on Twitter @alexiskweed.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn,YouTube, and reddit.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn,YouTube, and reddit.